Participation in events such as the 81st Venice International Film Festival inevitably exposes one to an exercise in cinephilic bulimia: that is, an exercise that can involve eight or more hours spent watching different films the same day. The consequences can be of two types. Either an anesthetization that leads to confusing the various films, in a sort of patchwork made of images, colors, plots and characters that are more or less superimposable. Or, on the contrary, a nervous fatigue that facilitates the polarization of enthusiasm or vice versa of antipathy, adhesion or repulsion. But the authentic cinephile sooner or later does not give up the moment of truth, the one in which he asks himself what he has really seen and therefore what judgment there is to draw from it. Here are some examples of the results that the undersigned has reached.

“Campo di battaglia”, directed by Gianni Amelio, 103 min., Italy, Production: Kavac Film (Simone Gattoni, Marco Bellocchio), Ibc Movie (Beppe Caschetto), One Art Film (Bruno Benetti) with Rai Cinema

I’ll immediately mention some of my favorites seen during this Exhibition. First of all, two Italians, with a historical theme: Leopardi, the poet of infinity by Sergio Rubini and Campo di battaglia by Gianni Amelio. The first, a true blockbuster destined to become a television series, is a bit surprising in that it followed the film on the exact same theme directed by Martone only ten years ago, but so much the better: the comparison can only benefit similar works, both original and stimulating as well as proposing significantly different angles on this poet who has never been celebrated enough. The second film, freely inspired by the novel La Sfida by Carlo Patriarca, also includes Marco Bellocchio among its producers and offers a convincing and shocking picture of the situation in a military hospital during the First World War and the spread of the devastating Spanish flu epidemic. The enormous masses of anonymous corpses, the unspeakable suffering of the wounded, the obsessively repeated imperative of “war as a duty” and yet also the desperate will to escape it: such and so many are the suggestions offered by this film that invite us to meditate on the warmongering manias increasingly present in our time. The acting of Alessando Borghi in the role of the protagonist is highly appreciable.

“Quite life”, directed by Alexandros Avranas, 99 min., France, Germany, Sweden, Greece, Estonia, Finland, Production: Les films du Worso (Sylvie Pialat, Alejandro Arenas Azorin, Benoît Quainon), Elle Driver (Adeline Fontan Tessaur ), Fox in the Snow Films (Olivier Guerpillon, Frida Hallberg), Senator Film Produktion (Reik Möller, Ulf Israel), Amrion (Riina Sildos), Playground (Kostas Sfakianakis), Asterisk (Vicky Miha), Making Movies (Kaarle Aho)

Also worthy of mention are the two French films Quite life by Alexandros Avranas and Leures enfants, après eux by Ludovic and Zorau Boukherma, both concerning the ways in which Westerners relate to populations of foreign origin. The first film focuses on the vicissitudes of a family that fled Russia and sought asylum in Sweden[1]. One of many real cases – as explained in the credits – in which children of foreign origin, losing all hope for the future together with their parents, fall into a real state of coma that is not always reversible. A “true” story, therefore, but represented with great pathos and even hints of irony by the team directed by Alexandros Avranas. As for Leures enfants, après eux, it is based on the novel of the same name by Nicolas Mathieu, winner of the Prix Goncourt, set in a valley in eastern France, a former steelworks area that has long been abandoned, where young natives have relationships that are sometimes deeply hostile with the children of immigrants who have now settled down, in a jumble of personal and collective dramas with an uncertain outcome. All narrated in a dry and engaging way.

“The New Year that Never Came”, directed by Bogdan Muresanu, 138 min., Romania, Serbia, Production: Kinotopia (Bogdan Mureșanu), All Inclusive Films (Vanja Kovacevic)

Particularly well-crafted and even funny is the plot of the Romanian film The New Year that Never Came by Bogdan Muresanu. What is evoked here is a jumble of various personal events that end with the famous rally in Bucharest on 22 December 1989, when the fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime began. In terms of themes, but also in narrative style, Muresanu seems to be inspired by that great master of Polish cinema Andzej Wajda, director of the unforgettable Człowiek z marmuru and Człowiek z żelaza, as well as a witness to Solidarnosc and the fall of the pro-Soviet regime of Jaruleski. It is surprising then that the director of The New Year that Never Came, despite the humour and intelligence so demonstrated and despite the implicit references to Wajda’s teachings, admits to being incapable of understanding why even among Romanians today not everything from the socialist past seems condemnable [2].

“Trois amies”, directed by Emmanuel Mouret, 118 min., France, Production: Moby Dick Films (Frédéric Niedermayer)

Another film where the imprint of a predecessor is very recognizable is Trois amies by director Emmanuel Mouret. A plot of events, confessions, misunderstandings and sentimental adventures of three friends, precisely, that cannot fail to recall the genre of film of which Eric Rohmer was a master. Mouret’s clear intent is to induce the audience to identify with figures as close as possible to the average of those more or less well-off and settled in a European city like Lyon. A fundamental resource to enliven the plot is to make it take a surprising turn just when its development seems most predictable. A somewhat mannered artifice that avoids the risk of banality sometimes run by this film, still enjoyable, but certainly not aimed at exploring the mysteries of amorous passions, as one might hear said.

“To Kill a Mongolian Horse”, directed by Xiaoxuan Jiang, 98 min., Malaysia, USA, Hong Kong, South Korea, Japan

A separate discussion is instead deserved by To Kill a Mongolian Horse, the first work by the Mongolian Xiaoxuan Jiang, which tells of the increasingly sad and painful living conditions to which the inhabitants of the endless grasslands, such as sheep, horses and herdsmen of Chinese Inner Mongolia, are forced. Superb photography accompanies the narration of an almost documentary imprint, but at times interrupted by surprising sequences between the dreamlike and the symbolic, while the ever-sparse acting enhances the denunciation of the existential precariousness to which this country is reduced. The aggression it has suffered due to increasingly adverse climatic conditions, but also following transformations of the territory dictated by speculative operations seems to leave tourism as the only humiliating opportunity for survival for the residents. Drinking on it, to the point of the most extreme hangover, is the last disheartening, yet ironic word of this appreciable work.

“Why war”, directed by Amos Gitai, 87 min., France, Switzerland, Production: Agav Films (Amos Gitai, Laurent Truchot), Agav Hafakot (Shuki Friedman), Elefant Films (Alexandre Iordachescu)

The review could obviously be much more extensive, but this is what most struck the writer in a positive sense. A note of demerit cannot, however, be missing. Without mentioning the pretentious, confused, as well as politically ambiguous, Why war by Amos Gitai, a mention must be made of Wolfs by Jon Watts, a pure and simple “game” of the two so-called kings of Hollywood, Brad Pitt and George Clooney. Two actors who are sometimes engaged in more worthy causes – just think of the acting of the first in the notable War Machine (2017) by David Michod and the direction as well as the acting of the second in Le Idi di marzo (2011) – but this time truly reunited only for trivial reasons. One could also say that it is one of those usual low-quality soups prepared and served in a hurry by the greatest film industry in the world, but in times of war like ours it is truly annoying to see many things that this film takes for granted. For example, making fun surrounded by a sea of still smoking corpses, but exhibited and treated as irrelevant because they belong to gangs of “Albanians” and “Croats”, it goes without saying supercriminals. Or that being a professional killer does not exclude the fact of presenting oneself as a great funny guy. Now is the time, however, to leave the scene to the question that increasingly pressing hovers over this 81st Venice International Film Festival towards its final stages: who will win?

[1]. In that Sweden, whose atrocious eugenic policies based on the supposed science of racial biology and adopted in this country for more than forty years from 1934 to 1976 are too often forgotten. https://it.euronews.com/2023/06/08/1934-1976-eugenetica-in-svezia-oltre-20mila-sterilizzazioni-forzate

[2] https://variety.com/2024/film/global/in-the-new-year-that-never-came-bogdan-muresanu-trailer-1236121362/

Info:

https://www.labiennale.org/it/cinema/2024

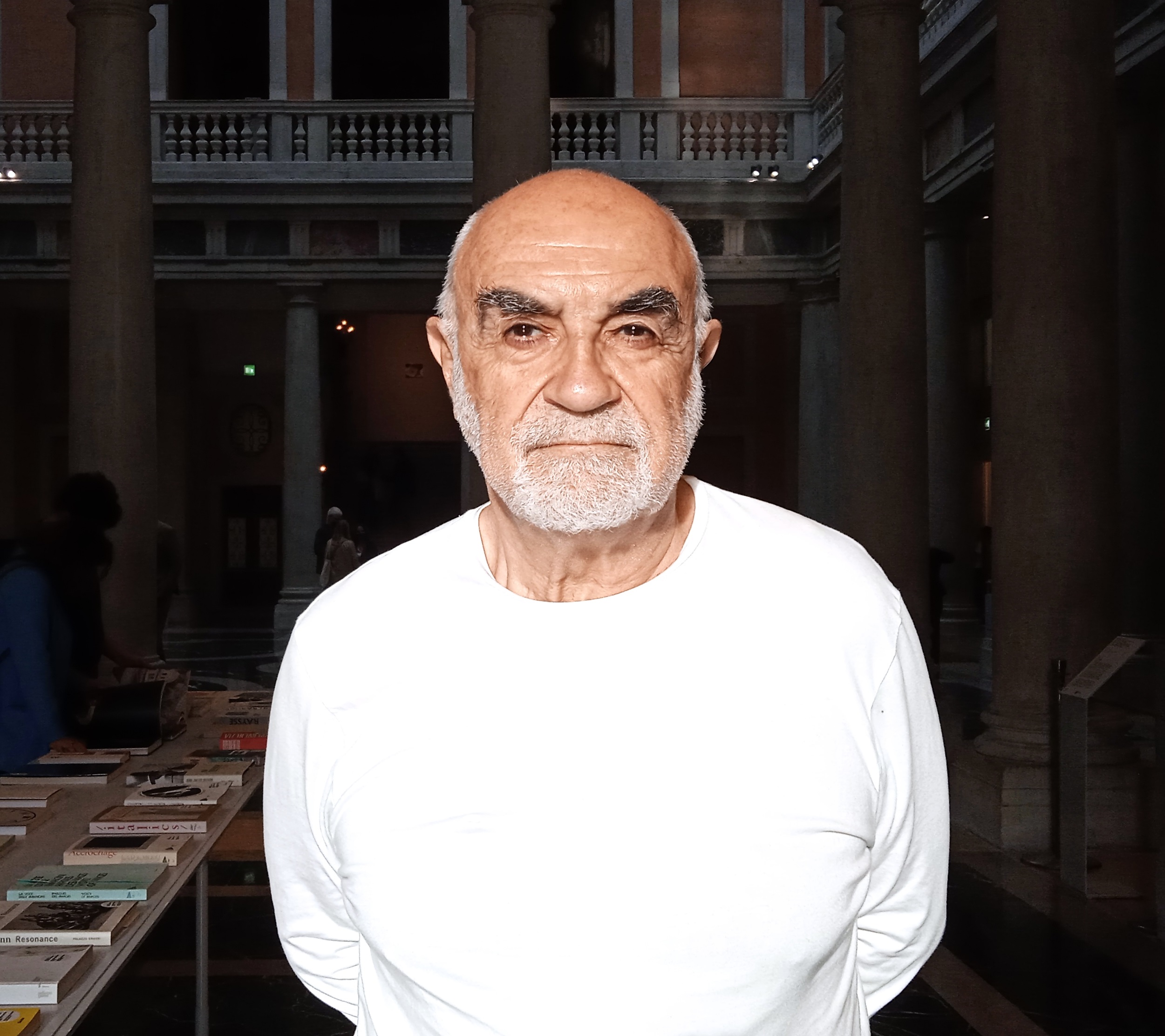

Cover image: President Pietrangelo Buttafuoco (Ph. credits La Biennale di Venezia – Foto ASAC)

Valerio Romitelli (born in Bologna in 1948) taught, researched and lectured in Italy and abroad. His disciplines: History of political doctrines, History of political movements and parties, Methodology of the social sciences. Among his latest publications: L’amore della politica (2014), La felicità dei partigiani e la nostra (2017), L’enigma dell’Ottobre ‘17 (2017), L’emancipazione a venire. Dopo la fine della storia (2022).

NO COMMENT