The pacifists among whom I certainly side (but in a disenchanted way[1]) often ask themselves a question that seems unanswered: why war? In other words, why has humanity, in the course of its thousand-year civilizational career, not yet come to the point of giving up such a barbaric means as war? Or even worse: why have we even reached the point of civilizing war, in the tragically ironic sense in which from the Second World War onwards it has become a normal phenomenon that civilians killed in armed conflicts are more numerous than the soldiers themselves (as it is sensationally and horribly happening during the ethnic cleansing carried out by the Netanyahu government against the inhabitants of Gaza)?

Id., Usa/UK, 2024. Regia: Alex Garland. Interpreti: Kirsten Dunst, Cailee Spaeny, Wagner Moura, Stephen McKinley Henderson, Nick Offerman. Durata: 1h e 49′. Distribuzione: 01 Distribution, courtesy A24, DNA Films

If you want, however, there is a simple answer to these complicated questions. And it is that without some good universalistic idea capable of uniting the whole of humanity, it tends to divide more and more and the more it divides the more it ends up tearing itself apart according to ethnic or identity alignments, which in turn sooner or later inevitably degenerate into wars increasingly extensive and without limits. Too simple to be true? So it certainly appears to contemporary opinion, disillusioned as it is by the last two great universalist political ideas, which were first (until 1989) communism, then democracy (whose golden age began more or less precisely from that year is getting further and further away, as Colin Crouch[2] among others teaches.

Id., Usa/UK, 2024. Regia: Alex Garland. Interpreti: Kirsten Dunst, Cailee Spaeny, Wagner Moura, Stephen McKinley Henderson, Nick Offerman. Durata: 1h e 49′. Distribuzione: 01 Distribution, courtesy A24, DNA Films

This void of references that eliminates any capacity for analysis regarding the dark contemporaneity in which we have ended up is precisely what the film Civil War, direction and screenplay by Alex Garland (released this year and with considerable success also in Italy) narrates: it tells us about it, certainly not because it even vaguely alludes to the need to have some idea to understand wars and/or bring peace closer. But it tells it to us because, displaying the most absolute indifference to any rational inspiration, it shows how war, no matter how many horrors, deaths and destructions it entails, can currently be seen, perceived and experienced no more and no less like a senseless video game.

Id., Usa/UK, 2024. Regia: Alex Garland. Interpreti: Kirsten Dunst, Cailee Spaeny, Wagner Moura, Stephen McKinley Henderson, Nick Offerman. Durata: 1h e 49′. Distribuzione: 01 Distribution, courtesy A24, DNA Films

In the plot of this film, nothing at all is said about the reasons why the United States ended up in this Civil War. To convince the viewer of such a probability, the impressions left at the time by the images of the Trumpian assault on Chapitol Hill on January 6, 2021 or the frequent news reports on the disputes that now seamlessly divide everything and everyone (states, parties, cultural alignments and simple citizens) in Washington’s homeland. What remains is that something as sensational and complicated as a no-holds-barred armed conflict within the world’s greatest military power could be represented in the same way as a sci-fi invasion of aliens could be. Not a single mention is made, among other things, of the evidently most terrible and urgent issue in similar circumstances: the possibility of resorting to the massive arsenal of atomic bombs of which the United States isthe largest possessor in the world. None of the different warring factions seems to have thought about it.

Id., Usa/UK, 2024. Regia: Alex Garland. Interpreti: Kirsten Dunst, Cailee Spaeny, Wagner Moura, Stephen McKinley Henderson, Nick Offerman. Durata: 1h e 49′. Distribuzione: 01 Distribution, courtesy A24, DNA Films

Guiding the spectator through the infernal circle of shootings, shelling, massacres and various killings is provided by a quartet of journalists, needless to say, brought together more by chance than by choice in an impromptu team, with a composition that cannot be more obvious than that: the old fat and altruistic black man, the dumb girl but with a brilliant future, the man a little rude, realistic but without charm, the woman, this one fascinating, but too worn out by previous experiences on war theaters. All narrated according to the very obvious scheme of the stars and stripes road movie. Watching Civil War therefore finds oneself immersed in a sort of travel experience into the deepest and most terrible chaos, of which the protagonists are careful not to even try to understand and discuss the deepest causes. Their only priority is to take as many high-impact photos as possible: it goes without saying, even better if they are gruesome and shocking. The coveted final objective is obviously the scoop of scoops. In fact, what could be driving our four journalists to travel by car from New York to Washington despite the infinite and abysmal looming dangers? Obviously it can’t be anything other than the intent to meet, photograph and interview him: yes, him, the president in flesh and blood, holed up in a super militarized White House!

Id., Usa/UK, 2024. Regia: Alex Garland. Interpreti: Kirsten Dunst, Cailee Spaeny, Wagner Moura, Stephen McKinley Henderson, Nick Offerman. Durata: 1h e 49′. Distribuzione: 01 Distribution, courtesy A24, DNA Films

The ending will therefore consist, naturally, in confirming all the nihilism flaunted in the film from the beginning. That the rot of the rot, the cause of all evil and therefore of the Civil War, is right at the top of state power is a morality which can never displease the people of the so-called “largest democracy in the world”, as well as its vassal countries such as ours. In conclusion, it should not be forgotten that Alex Garland, author of Civil War, can boast a very respectable biography: as well as director and screenwriter of other well-known films (such as Ex Machina in 2015 and Annihilation in 2018) he is also a writer of books success like The beach, on which the famous film by Danny Boyle with Leonardo DiCaprio as the protagonist was based. To adequately weigh the merits and defects of this latest effort, it would therefore be advisable to rethink it in the light of his entire remarkable career. However, the doubt remains that Civil War will not be his most convincing film.

[1]https://www.machina-deriveapprodi.com/post/per-un-pacifismo-disincantato

[2] Postdemocrazia, Roma-Bari, laterza 2003

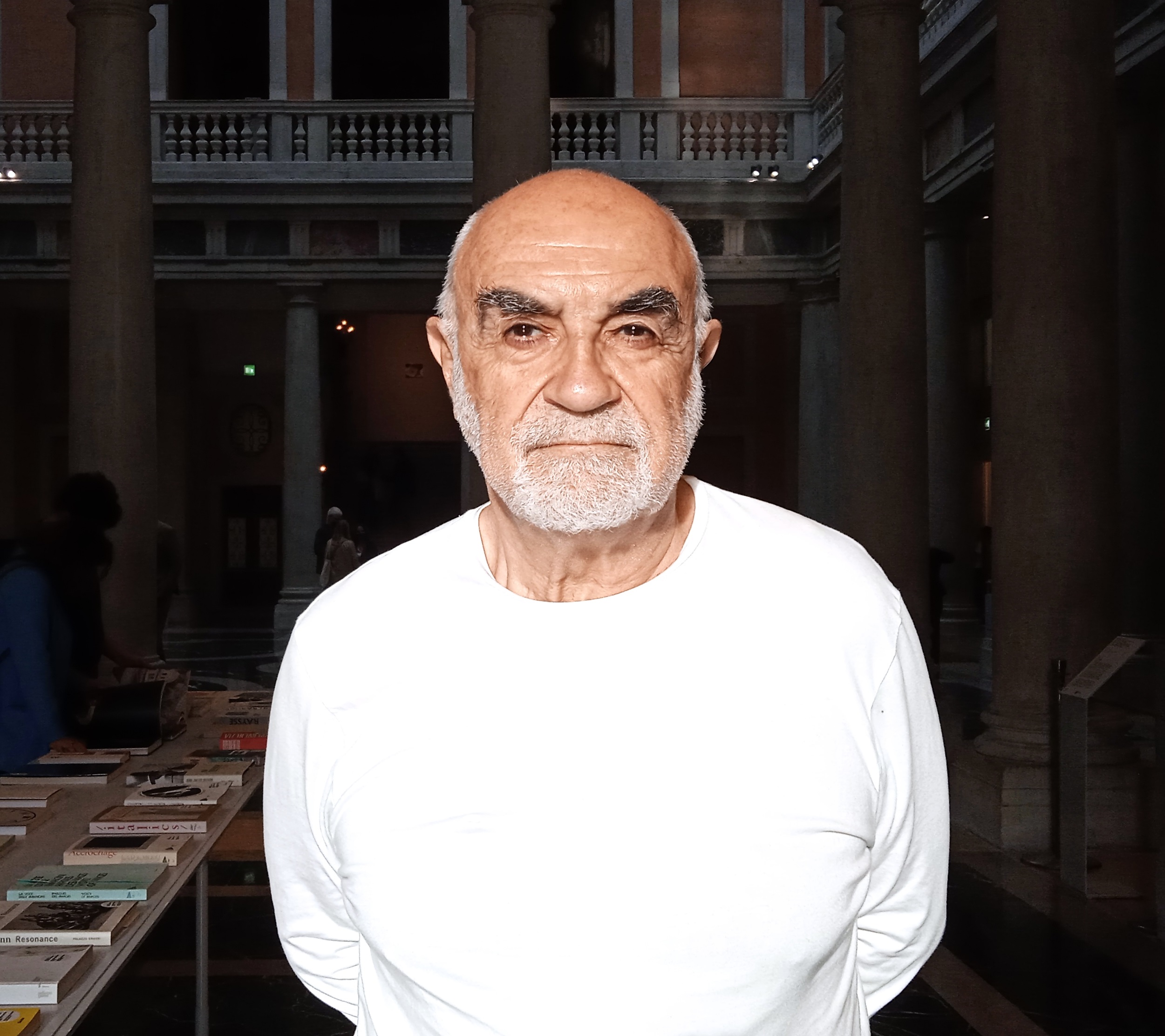

Valerio Romitelli (born in Bologna in 1948) taught, researched and lectured in Italy and abroad. His disciplines: History of political doctrines, History of political movements and parties, Methodology of the social sciences. Among his latest publications: L’amore della politica (2014), La felicità dei partigiani e la nostra (2017), L’enigma dell’Ottobre ‘17 (2017), L’emancipazione a venire. Dopo la fine della storia (2022).

NO COMMENT