There can be no more gory reality than any war that is never “the first” as Brecht would say. Every war must be told. Indeed, all wars should be gutted in their ruthless grammar of destruction, panic, annihilation, inhumanity and atrocious suffering.

It is fundamental to ask ourselves how all wars – or some in particular – are perceived by those who are capable of “dipping their pen in the darkness of the present”[1].

It would seem that all the ability to remember the fragility of existence and the continuing possibility of developing empathy towards all those fleeing wars and any other form of violence would be up to art. But art does not always fulfill this function, especially contemporary art.

Several contemporary artists argue that they do not want to deal with political denunciation because they believe that art has other priorities and cannot replace politics.

Reflection that would pave the way for a fertile debate, from which the concept of “contemporary” could be extracted as one of the filters, from which a certain idea of art emerges that tells and denounces this world made up of martyrs, abuse, wars, death.

If there is a time to dream of the infinite possibilities of art, there is also a time, no less important, to measure the inhumanity of humanity and the greed for power and money that has dismembered far and near places: raped, bombed, annihilated. Think of Syria, Palestine, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Ukraine, the tragedy of the dead in the Mediterranean. And to so many wars going on at this moment in different parts of the world.

So what can contemporary art do? On the one hand, restoring the dreamlike imagination of beauty made up of “milk and dreams”, like what is being prepared for the next Venice Biennale, on the other hand, proposing critical thinking. That it is also of a political and social nature.

If we talk about art, we are not just talking about dreams but about inclusion and elimination of any prejudice linked to culture, religion and gender. Only in this way a part of contemporary art can rise without barriers, without censorship, capable of leading us towards a catharsis of reflection on the world in order to defend a certain idea of the world.

So, we think of artists who have made works of political denunciation such as the Italian Davide Dormino, a well-known sculptor, with his itinerant and interactive installation, in bronze, “Anything to say”.

Dormino’s work was born from an idea of Charles Glass, a journalist involved in international politics, who wanted to focus attention on three examples of contemporary revolutionaries such as Edward Snowden, Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning. These characters are considered controversial heroes because they are able to make their voices heard in the face of the atrocities of war crimes, with the strong courage that distinguishes them in not wanting to indulge a control system that involves us all in our lives.

Thus Dormino proposes, in his itinerant installation that has already crossed the most important European squares, the three bronze sculptures of Snowden, Assange and Manning at natural height and then an empty chair to pick up those who have the courage to see beyond and place side by side these contemporary heroes. A strong message to draw attention to issues of international politics that concern us all.

Or, going far back in the years, the image of Marina Abramović‘s performance, Balcan Baroque, against the war in Yugoslavia is clear and now iconic. It was 1997 and with this performance she won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale as “best artist”.

This is another example of an interactive work. In this case, the spectators had to reach a staircase to arrive in a large, dimly lit room, where a calculated sense of disgust awaited them, linked to the strong smell of rotten meat. The vision of the performance was given by the artist who sat – in a white tunic stained with red – on a pile of bleeding bones of oxen, a symbol of war, for six hours a day and for three days.

In this performative action Abramović was seen taking the bones, one by one, trying to remove any traces of blood with a metal brush and soap and water.

Another powerful message to the public, not only to displace them but to move that idea of condemnation towards the brutal violence of the war on the Balkans, which like any war cannot be canceled because it is another sign of martyrdom on the bones of the world.

Just as universally symbolic is Pablo Picasso‘s work Guernica, created after the bombing of the Basque town in April 26, 1937.

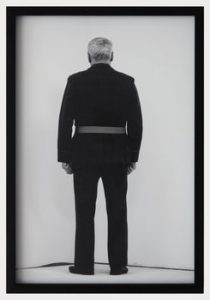

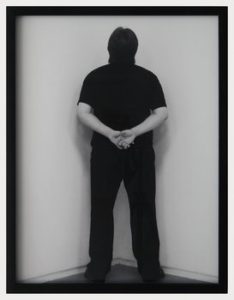

And to return to our days, the artistic research of the Spanish artist Santiago Sierra wants to testify to the shameful deviance of injustices and wars, with black and white images where “war veterans” do not even turn their gaze to the viewer. They are immortalized from behind in a ghostly minimal way since the war itself is a nefarious destruction carried out by men who no longer have eyes, having turned their backs on life itself.

At this point of the speech, one cannot fail to mention Banksy who has often expressed his political denunciation against the war such as his work of 2017: “Civilian Drone Strike” or three drones that destroy the drawing made by a little girl, in which it is portrayed a little girl who with her dog looks in dismay at her bombed-out house.

These are just a few examples of that ruthless cry of a certain idea of contemporary art that stands against the horror of all forms of violence. A cry that does not know the finitude of time, but goes beyond remaining a necessary evocation of peace and hope for a different world and not to forget that “the war to come is not the first”.

To remind us to get on an empty chair and shout our defense on the world so that the bones of humanity are not always dipped in blood.

[1] Giorgio Agamben, Che cos’è il contemporaneo, Roma, Nottetempo editore, collana “I Sassi”, 2008, cit. p. 13

Info:

Davide Dormino, Anything to say, Lunerse, Austria 2020, Photo Luca Tiefenthaler, courtesy the artist

Davide Dormino, Anything to say, Lunerse, Austria 2020, Photo Luca Tiefenthaler, courtesy the artist

Davide Dormino, Anything to say, 2021, mixed media on paper, 100 x 70 cm, courtesy the artist

Davide Dormino, Anything to say, 2021, mixed media on paper, 100 x 70 cm, courtesy the artist

Santiago Sierra, Veteran of the War of Afghanistan facing the corner. Art Point, Donetsk, Ukraine, 2011; Fotografia, b/w lambda print on dibond, 60 x 40 cm, courtesy of the artist and Prometeo Gallery Ida Pisani, Milan-Lucca

Santiago Sierra, Veteran of the War of Afghanistan facing the corner. Art Point, Donetsk, Ukraine, 2011; Fotografia, b/w lambda print on dibond, 60 x 40 cm, courtesy of the artist and Prometeo Gallery Ida Pisani, Milan-Lucca

Santiago Sierra, Veterans of the Wars of Afghanistan, Iraq and Northern Ireland facing the corner, 2011; Fotografia, b/w lambda print on dibond, 60 x 45 cm, courtesy of the artist and Prometeo Gallery Ida Pisani, Milan-Lucca

Santiago Sierra, Veterans of the Wars of Afghanistan, Iraq and Northern Ireland facing the corner, 2011; Fotografia, b/w lambda print on dibond, 60 x 45 cm, courtesy of the artist and Prometeo Gallery Ida Pisani, Milan-Lucca

Through art she feels the need to get closer to nature, deciding to create an artistic residence on Etna as a “refuge for contemporary art” for artists and scholars. Thus was born Nake artistic residence. She won the Responsible Etna Award 2015. In 2017, she was invited to the Sala Zuccari, Senate of the Republic, as an art critic. She writes for Italian and foreign artists. Curator of the first Museum of Contemporary Art of Etna and of the “Contemporary Etna” project.

NO COMMENT