Cijaru’s is a return story. It is the desire to question the narrative of one’s own land. It is belonging to elsewhere. Davide De Notarpietro and Francesco Scasciamacchia are two migrants. Maria Domenica Rapicavoli is a migrant. They believe in art, in change. The Torre Matta di Otranto is the chosen stage. The Make This Earth Home exhibition (26 / 6-3 / 11/2020) was the first act.

Cijaru recently launched a crowfunding campaign – on Kickstarter – to finance the publication of the catalog. The volume would deepen the topics covered by the exhibition, fulfilling the functions of secondary use and archival material. We talked about it with them.

Jacopo De Blasio: Art is getting closer and closer to anthropology. It often returns an ethnographic impulse, documentary suggestions. Maria Domenica Rapicavoli’s works look to the past to address issues that are very current and central to contemporary debate. Do you believe that this is a decisive step for the reaffirmation of art as a relational practice?

Cijaru: Relational art as theorized by Nicolas Bourriaud at the end of the 90s has as its object the social relations that are activated by a sculpture, an installation, a video and a performance. We do not believe that Maria’s works presented at Torre Matta are a reaffirmation of this type of art, but rather that they are the aesthetic result of interdisciplinary practices, that is, those practices that use other disciplines within the artistic discourse. When artists look for a space of autonomy and self-assertion, they include disciplines other than their own: a typical feature of the artistic avant-gardes, think for example of the inclusion of dance in the visual arts. Artists go beyond disciplinary boundaries to experiment, question canons and practices that are a limit to their free expression of thought. In the case of Maria D. Rapicavoli’s “Make this Earth Home” exhibition at Torre Matta, for example, the works are the expression of anthropological, ethnographic, archaeological and historical research. Thanks to the use of these different disciplines, Mary’s art allows a critical narration on the ways in which, for example, history is constructed and disclosed. We believe that if contemporary art becomes a storytelling device, in our case above all related to local history, it can generate questions, doubts and reversals of thought.

“Glocal” art has often been talked about, both to describe the application of global strategies at local conditions, and for the introduction of local content in the global market. In this sense, should female artists and artists act as social aggregators?

We do not believe in this clear-cut “global / local” distinction or in its complete hybridization into what many call “glocal”. What we think, however, is that there are works of context that speak to that context and works that, on the other hand, are not “situated” and express the so-called “universal values”. We think that the problem is not the global or the local but precisely this ‘universalist’ paradigm which should not belong to either art or the social sciences, or perhaps it should not even belong to what we believe to be “hard sciences” as objective and therefore, universal. We remember the group of artists / activists Act-up for having questioned the scientific paradigms regarding the HIV epidemic and its treatments, methodologies, etc. or for example the Critical Art Ensembles that put scientific research under a magnifying glass, not only by criticizing absolute and universal values, through relativism but also by proposing another way of doing “science”. We respond to the second question by proposing that art itself, if understood also as an ordinary culture and not as a mere aesthetic exercise, can be a social aggregator and or even an equalizer (a social leveler).

Streaming is at the center of cultural fruition. After the recent restrictions, the digitization of everyday life is even more relevant. In your opinion, will paper catalogs become objects for amateurs like vinyls or DVDs?

Without going into precise speeches on such a complex question, the idea of a paper catalog, like the one we are trying to produce through a crowdfunding campaign, is simply an answer to this extreme intangibility of our lives. We have to make a comparison: it is as if craftsmanship and manual work, which we consider social practices and therefore culture, were a response to the use of high technology in visual art. In a certain sense, the return to low-density “technological” practices and ways, such as terracotta pots, papier-mâché molds or the catalog of “Make this Earth Home” are a way to claim another existence, which is disappearing. In all the processes of economic, social and political change, such as the ones we are experiencing, ways of life are canceled out, but continuing to exist in the shadows they position themselves as alternative and opposition practices. Perhaps, naively (someone told us genuine) this is the resistance that cijaru is practicing.

The project will be funded only if it reaches its goal by 20/3/2021. Why did you decide to launch an “All or Nothing” campaign?

We like challenges and then we didn’t have many options for an art catalog. We desperately searched for an Italian crowdfunding website that specifically had art publishing within the categories and a website that all our Italian and foreign friends knew and considered reliable, but we didn’t find it in the time we had set. So we followed Kickstarter’s policies, trivially.

Make This Earth Home strongly involves the local community. In a certain sense, it supports the economy. Give and take. Do you believe that this exchange should go hand in hand – if not precede – with the possibility of obtaining institutional funding?

During the so-called “second epidemic phase” period, at the end of the exhibition, we had the opportunity to reflect on what the “Make this Earth Home” project had been and we only realized ex-post that one of the unplanned actions had been to have activated local economies on many fronts. An act that we performed without a strategy or an aim but simply with the idea of a context project and for the context. We involved not only the artisans (papier-mâché, terracotta and Lecce stone) but also a communication and events agency, a screen printing, a light-designer, a web designer, etc. and in general all citizenship. We created a local community that felt an integral part of the project. Regarding the institutional funding, at least the regional ones in which we participated through a tender, they were not received. This made us take other paths and in the name of that community we have launched a crowdfunding campaign in which we invite you to participate.

Mandatory question: are you already planning something for the future?

Despite the pandemic situation, we are working on a project on the material culture of the Byzantine period that strongly characterized the area, commissioned to the Greek artist Maria Papadimitriou and the curator Gabi Scardi. We have also been working for some time in collaboration with the a.titolo collective on an urban redevelopment project in the 167b area of Castrignano dei Greci in the Salento Grecìa.

Info:

Maria D. Rapicavoli, Make this earth home, 2020; flex led neon e plexiglass; 700 x 80 x 20 cm; edificio adiacente la Cappella della Madonna dell’Alto Mare, Otranto. Foto: Raffaele Puce

Maria D. Rapicavoli, Make this earth home, 2020; flex led neon e plexiglass; 700 x 80 x 20 cm; edificio adiacente la Cappella della Madonna dell’Alto Mare, Otranto. Foto: Raffaele Puce

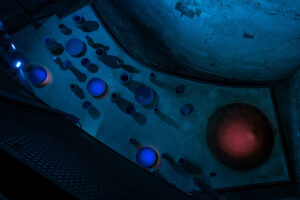

Maria D. Rapicavoli, I due mari e Fuoco, 2020; veduta dell’installazione per la mostra personale “Make This Earth Home”, Torre Matta, Otranto 2020. 35 vasi di terracotta smaltata lavorata a mano e acqua marina; dimensioni variabili; terra di bauxite; Ø 3.50mx1.60 cm, courtesy: l’artista

Maria D. Rapicavoli, I due mari e Fuoco, 2020; veduta dell’installazione per la mostra personale “Make This Earth Home”, Torre Matta, Otranto 2020. 35 vasi di terracotta smaltata lavorata a mano e acqua marina; dimensioni variabili; terra di bauxite; Ø 3.50mx1.60 cm, courtesy: l’artista

Maria D. Rapicavoli, Terra#1, 2020; opera installata presso Lungomare degli Eroi, Otranto per la mostra personale “Make This Earth Home”, Torre Matta, Otranto 2020, pietra leccese scolpita; 178x160x45 cm, courtesy: l’artista, foto: Raffaele Puce

Maria D. Rapicavoli, Terra#1, 2020; opera installata presso Lungomare degli Eroi, Otranto per la mostra personale “Make This Earth Home”, Torre Matta, Otranto 2020, pietra leccese scolpita; 178x160x45 cm, courtesy: l’artista, foto: Raffaele Puce

Maria D. Rapicavoli, Il suono dell’aria, 2020, cartapesta e suono registrato; 55 x 26 x 30 cm, courtesy: l’artista, foto: Raffaele Puce

Maria D. Rapicavoli, Il suono dell’aria, 2020, cartapesta e suono registrato; 55 x 26 x 30 cm, courtesy: l’artista, foto: Raffaele Puce

Maria D. Rapicavoli, Make this earth home, 2020; flex led neon e plexiglass; 700 x 80 x 20 cm; edificio adiacente la Cappella della Madonna dell’Alto Mare, Otranto. Foto: Raffaele Puce

Maria D. Rapicavoli, Make this earth home, 2020; flex led neon e plexiglass; 700 x 80 x 20 cm; edificio adiacente la Cappella della Madonna dell’Alto Mare, Otranto. Foto: Raffaele Puce

Jacopo De Blasio (Rome, 1993) graduated with honors in art history from the “La Sapienza” University in Rome, currently assistant librarian at MAXXI in Rome. He was a collaborator of the artist Maria Dompè and cultural mediator at Palazzo delle Esposizioni. Independent curator, he mainly deals with the relationship between contemporary art and society.

NO COMMENT