On the occasion of the bi-personal exhibition “Holobiont Rhapsody”, a dialogue between the Eastern European artist, Stach Szumski (Danzica, 1992), and the Italian, Francesco Pacelli (Perugia, 1988) curated by Eastcontemporary in Milan, we had a dialogue with Claudia Contu, a young critic and curator, who wrote the critical text that accompanies the exhibition. Invisibility, writing for art and viral languages may perhaps save us from a despotic future.

Federica Fiumelli: In this exhibition of painting and sculpture we talk about organisms: viruses, bacteria and everything that surrounds us and that we cannot immediately grasp. A situation similar to the one we have been experiencing for a year now, in full health crisis, but also humanitarian, social and cultural. Could you tell us briefly and again the importance of the invisible?

Claudia Contu: Ciao Federica, that’s a really good question to start with. I would say the invisible is what glues our reality together and yet it’s easy to forget about it while carrying on with daily life. In writing a text for this show, I tried hard to stress that the invisible has a presence therefore it’s an agent that does things and it is done; it creates and is created. We understand this when we learn that mushrooms can feel us walking through a forest. Or, as you mentioned, when a deadly virus comes to agitate our economy, our social order, our individual and collective psyche. Everyone might have a different opinion over the importance of the invisible. However, I was hoping that the text could inspire broader questions about how the invisible leaves traces or manifests. Because, as Europeans, we hold a patriarchal and colonial past that still causes even greater disruptions to the lives of other people across the globe. As heirs of a society of colonisers, we are surfing on a chain of exploitation — quite literally, as I’m typing on a computer whose components were excavated in Congo. We are all about invisible networks, infrastructures and so on. So, what else is invisible in everyday discourse, and why? What else are we turning a blind eye to, or forgetting about? In other words, what is our responsibility over the importance of the invisible?

Can art writing be viral? Can and should it change in your opinion? Can the body of critical language metaphorically be celebrated as an “Holobiont Rhapsody”? Or, instead, as a critic and curator, do you find a contemporary problem of the flattening of language?

I don’t necessarily think that language is flattening because language is ever-changing by nature and always finds new, effective ways to construct meanings. I wasn’t surprised by the fact that individual emojis now feature in one of the biggest dictionaries and critical language should be able to make treasure of these opportunities. The problem for me lies more in meaning itself. In other words, the ideas and values we convey through language. It’s a crisis that has been around for a while and has favoured the art world’s creation of cryptic languages that make meanings confusing or difficult to understand. The ‘body’ of language certainly has parallels with a holobiont. Both imply ideas of coexistence, transformation and extra-species mutualism. Which is the best thing that could happen to language and meaning. You ask whether art writing can be viral and that’s a nice image — writing as a virus, spreading from one consciousness to another, mutating thoughts and habits. To answer this, I will go back to Internet culture: there isn’t a meme that Urban Dictionary won’t explain to you. It would be great if art writing could be like that.

What relationship do you establish with the artists you work with? How do they live your writing, your reflection on their art?

About five years ago, I was enamoured with the idea of creating community through art (I’m looking at you, Pasteurelli ❤︎) and that ideal persisted even after having graduated, moved to another country and worked with different people. Hanging out in studios, visiting shows together, having dinners with artists etc. you know the drill. The relationship had to be wholesome in order to build a significant collaboration with artists but also curators, and so on. I recently realised that it was, in many ways, an illusion and the way I was chasing it had become emotionally overwhelming. So, I am still finding out the right mix of folks and behaviours needed in creating the kind of artistic kinship that I still hold very dearly. Plus, 2020 made change compulsory, so it was time to cleanse. In fact, for the text of Holobiont Rhapsody, I haven’t met Stach, nor Francesco. Also, due to time constraints, we didn’t have a chance to exchange resources, conversations and ideas beforehand. But, thanks to the brilliant mediation by Agnieszka and Julia from eastcontemporary, I felt confident that I knew what the artists were envisioning when writing began. I can’t say what their thoughts on my writing are — positive, I shall hope! For me, writing about someone else’s work is an act of facilitation for the reader but also unpacking, identifying and contextualising patterns expanding from the work into society. I think that’s a responsibility that all art writers have nowadays.

You concluded the critical text with a very interesting question that I turn to you: could we speak the language of mushrooms and lichens in the future?

I grew up watching anime, reading manga and playing video games. Even though I have avoided disclosing this piece of information for quite some time, there were aspects of East-Asian culture that stuck with me for a long time. More so, they actually contributed to generating the curatorial interests I have now, including human and non-human kinship. There are worlds like Princess Mononoke’s or Pokémon’s showing people who talk or understand spirits of the woods, animals and lots of other entities and gods. My feeling about this tells me that we most certainly already knew how to speak those languages but we have forgotten following global modernisation and colonial subjugation.

Info:

Foto ritratto di Claudia Contu

Foto ritratto di Claudia Contu

Francesco Pacelli, Abyssa, 2020, glazed ceramics, 22 x 28 x 55 cm, the courtesy of eastcontemporary and the artist Holobiont Rhapsody, Milan, 2020

Francesco Pacelli, Abyssa, 2020, glazed ceramics, 22 x 28 x 55 cm, the courtesy of eastcontemporary and the artist Holobiont Rhapsody, Milan, 2020

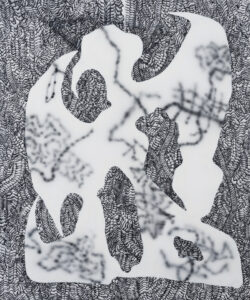

Stach Szumski, The Issue of Office Bacteria IV, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 150 x 180 cm, the courtesy of eastcontemporary and the artist, Holobiont Rhapsody, Milan, 2020

Stach Szumski, The Issue of Office Bacteria IV, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 150 x 180 cm, the courtesy of eastcontemporary and the artist, Holobiont Rhapsody, Milan, 2020

(1990) Graduated at DAMS in Bologna in Visual Arts with a thesis on the relationship and the paradoxes that exist between photography and fashion, from Cecil Beaton to Cindy Sherman, she specializes at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna in the two-year course in art teaching, communication and cultural mediation of the artistic heritage with a thesis on the historical-critical path of Francesca Alinovi, a postmodern critique. Since 2012 she has started to collaborate with exhibition spaces carrying out various activities: from setting up exhibitions to writing critical texts or press releases, to educational workshops for children, and social media manager. She has been collaborating since 2011 with various magazines: Vogue online, The Artship, Broken Fracture, Wall Street International Magazine, Forme Uniche Magazine.

NO COMMENT