What is your background?

My human and cultural background greatly owes to important personalities I met in the early seventies: I refer in particular to Gennaro Vitiello, a theater director with whom I spent, as an actor, three formidable years. Recently I published at Ombre Corte Palestre di vita, a tribute to him and to his amazing maieutic, to his great sensitivity as a man of culture. The experience with Vitiello, which I lived along with Silvio Merlino in the Libera Scena Ensemble, took us around Europe and our beautiful country in the period of the so-called cultural decentralization and later had a fruitful impact on a strictly artistic level starting from the establishment of the Ambulanti group. The other prominent person, and important reference point, was the architect Riccardo Dalisi. I think of the Rione Traiano, the papier-mâché laboratories, started together with the neighbourhood committees, involving children of the underclass. This too was a great training experience. After all, it is precisely there that I met, perhaps for the first time, the social, its contradictions, the problems and the dramas of a society subjugated by corrupt and greedy politics, a thousand miles away from the imperative concerns of people.

Can you tell us about Naples in the 70s?

Naples in the Seventies had a different image from the one of today, where the nightlife and the bed and breakfast seem to have the ball in hand. At the beginning of the seventies the whole tension of 1968 still lived on our skin. The political climate was very tense and we know how later it ended up with terrorism, of course not only locally. The art galleries, serving as landmarks, were Beppe Morra and Lucio Amelio’s; but the theatrical experimentation that took place in the basements was also popular. In short, there was a unique cultural ferment. There was a lively discussion about everything and many were the open doors to linguistic experimentation.

Do you remember any of the Ambulanti’s points of discussion?

The history of the Ambulanti is long and certainly can not be encompassed in a few lines. Now there are books dealing with that in a little more detailed matter. I can say that our group, as well as later other ones, did rotate independently, but also under Enrico Crispolti’s spur. We, the Ambulanti group, proceeded by analysis and by instinct. We were very clear about the importance of poetry: that is to say the maximum diapason that can be evocated by expressive languages. Moreover, unlike other groups conducting a more strictly political action, we did not want to sacrifice the linguistic dimension. Ours were poetic actions, as Crispolti himself defined them. Poetic actions strictly structured on the ephemeral. In fact, of those events today only some documentary photos remain. I recalled all this also at the conference organized by Lucilla Meloni last November at the Macro Asylum in Rome, focusing on the social art of the Seventies.

Later in 1976 you joined the Ambulanti group, at the Venice Biennale, in the section curated by Crispolti, Social environment. Tell us about the fish operation?

The Pesce rosso was a large object. Working with wicker and plasticized wire, I had created a light and strong structure shaped as a large fish, later called Pesce rosso. The skin consisted of a patchwork of colorful fabrics and socks left exposed, without glue and dough treatments. The scales were made with single, bent out socks. With that image I wanted to connect to the power of popular culture, to its festive and ritual manifestations. In Luca Palermo’s latest book Arte in movimento published by Postmediabooks 2018, I thus described the operation: “With the Pesce rosso I wanted to shake the minds of others, create a poetic flash, a gash in the compliance of daily perception. With that itinerant sculpture, which I later took to the 1976 Venice Biennale, I strolled along the beach corroded by the acids of Bagnoli, and even stepped into the water. People stopped, asked, we talked at length. The road was transformed day by day, more and more, into a laboratory. In short, for us, life, the relationship with the city and with others had to be strengthened by art, urging the myth-poetic dimension of the community. Art always plays a primary function because it creates an irreplaceable spiritual reality, the stronger the more participated. Also in the operation of via dei Mille (Natalevento, 1975) we acted this way, breaking with our appearances the automatisms that bind us to the at grand theater of everyday life”.

Do you think the rereadings taking place nowadays on the seventies seem exhaustive?

I must say that today the attenton to the seventies is remarkable. There are valuable researchers who are writing very meaningfully about those years. I think of Alessandra Pioselli, for example. She wrote L’arte nello spazio urbano, published by Johan and Levi in 2015; a very fundamental book because it is based on noteworthy intellectual honesty, reviewing all the groups that have worked in the social sphere up to today. I also think of Luca Palermo, a young professor at the University of Naples, who recently published at Postmediabooks Arte in movimento. Gli anni Settanta in Campania.

Don’t you think we should have the courage to link those experiences, although brief from a temporal point of view, but courageous from a substantial point of view, to research as radical as that of relational or participatory art?

Of course! But we should also have the courage to say that relational art by Nicolas Bourriaud is in debt with that of the Seventies. We should recognize the matrixes and the enormous historical importance of that phase, anticipatory yet revolutionary, and not to make believe with a nominally renewed formula that things started in the Nineties. Intellectual honesty is a fault of many foreign critics. Crispolti was long-sighted. You may like it or not, but things have gone this way. The great uproar of the Transavantgarde moreover diverted the attention on research based on the ephemeral and the gift, reproposing the object picture as a new dish to be inserted into the jaws of a market coming from long years of conceptual fasting.

Ernesto Jannini, Pesce rosso, intervento sulla spiaggia di Bagnoli (Napoli), 1976

Ernesto Jannini, Pesce rosso, intervento sulla spiaggia di Bagnoli (Napoli), 1976

Ernesto Jannini, Pesce rosso, intervento a Terzigno (Napoli), 1977

Ernesto Jannini, Pesce rosso, intervento a Terzigno (Napoli), 1977

Ernesto Jannini, Installazione in P.zza dei Consoli. Biennale di Gubbio 1979

Ernesto Jannini, Installazione in P.zza dei Consoli. Biennale di Gubbio 1979

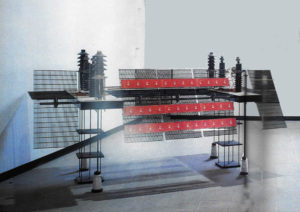

Ernesto Jannini, Grande Decartesiana, opera esposta alla Biennale di Venezia del 1990. L’opera è ora in collezione allo SPACE di Lugugnana di Portogruaro

Ernesto Jannini, Grande Decartesiana, opera esposta alla Biennale di Venezia del 1990. L’opera è ora in collezione allo SPACE di Lugugnana di Portogruaro

Ernesto Jannini, Equilibridi, 2009, installazione a Castel dell’Ovo, ph G.Carozza

Ernesto Jannini, Equilibridi, 2009, installazione a Castel dell’Ovo, ph G.Carozza

He is editorial director of Juliet art magazine.

NO COMMENT