«Un cane riconosce sempre il potere a fiuto […] il comando, l’obbedienza, le pause tra il bastone e la carezza». (Tiziana Villani, Corpi Mutanti, p. 89)

He does not bite. Despite his bloodshot eyes and nostrils flared like highways, in a gnashing that tears the muzzle on paper. The howl of the dog in He Doesn’t Bite II (2022) by Matei Vladimir Colteanu (Romania, 1997) recalls a ’53 study by Francis Bacon: the one with Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X as its subject. For Bacon, the head was the place of indiscernibility between man and animal; the mouth the black hole from whose darkness a growl is generated that takes us back to a rabid body, that of the mute, the dog. «The scream that comes out of the Pope’s mouth and the pity that comes out of his eyes have meat as their object»[1] Gilles Deleuze wrote some thirty years later about the screaming pope. And again, «Meat is the common zone of man and the beast, their zone of indiscernibility»[2].

Matei Vladimir Colteanu, He doesn’t Bite II, 2022, colored pencils on paper, 27×37 cm, courtesy the artist. Ph: Matteo Maino

Tiziana Villani’s Corpi Mutanti (2018), which luogo_e’s trio (Chiara Fusar Bassini, Federica Mutti and Luciano Passoni) has chosen as the leading volume for the collective exhibition Padrone e cane, takes us on a poetic and political reconnaissance of the link between dogs, humans and philosophy, tracing a literary relationship that starts with Plato’s Republic (380-370 b. c.), continues with Elias Canetti in Crowds and Power (1960) and reaches as far as the companion species pacts theorized by Donna Haraway (The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness, 2003). The dog is presented to us by Villani as the non-human species that, with humans, has shared a same, intense and long process of domestication, whereby the dog can never again be a wolf, but only a grown wild dog, and humans can never completely return to their animal nature. This systemic domestication has, in fact, intervened, for both species, on the repression and disciplining of all instincts not deemed suitable for the social process, for the practices of common sense, creating a “second body”, an institution-bound political body, which would seem to cancel out the “first body”, the one closest to animality, drives, desire, creativity, exploration. In a word, to the dog.

Gabriele Longega, Invokation of my ancestral demons for healing, 2022, leather, CD, cement, hair extension, fabric, approx. 95×60 cm, courtesy the artist. Ph: Matteo Maino

In Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X (Francis Bacon, 1953, Des Moines Art Center) it is the twisting that man has performed on himself, the stripping away from the species of origin that tears at the face of the animal-man, makes him rabid, makes him emit what is closest to barking: a cry. Bacon’s pope and Colteanu’s dog demonstrate that the organs of the “first body,” seemingly dormant, do not cease to ignite micro-ribellations in the “second body,” to want to escape. The two subjects undergo – on closer inspection – the same process of disorganization and smashing of the face. In Bacon, the head of the beast struggles coping with the human figure: the “features of vaulting”, that is, of the socially and culturally organized face, are liberated and become “features of animality”[3]. While, the dog’s teeth in He doesn’t bite II (2022) are more like human teeth than animal teeth: thicker and more regular, less sharp. The semblances of a man’s face come out from a dog’s head. In both cases, the snarling, shrieking mouth seems to be the line of escape from the organized, domesticated body, which we have called “second”: «The head-meat is a becoming-animal of man. In this becoming, the entire body tends to escape from itself»[4].

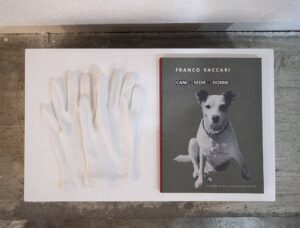

Franco Vaccari, Cani + sedie + donne, 2005, exhibition catalog (Faenza, Galleria Comunale d’Arte, 9 December 2005 – 15 January 2006) The notebooks of the artist’s circle, Faenza, private collection. Ph: Matteo Maino

An exhortation to migrate from everyday capitalist life, from the “second body” to the place of utopia and enjoyment, by becoming animals, we also find it in the piece Chihuahua (2003), the subject of Invokation of my ancestral demons for healing (2022) by Gabriele Longega (Venice, 1986). This is not the first time that Longega has reflected on the processes of domestication and animality, particularly in relation to the dimension of cruising between males: as if at that juncture, in that space of subversion of what exists, outside of socially capitalizable time, there is on the one hand a humanization of nature and, on the other, an animalization of the human. In Dog’s saliva web rectum pit (2022) strands of saliva, entangled in vegetation, served to connect a web of cursed images of demonic dogs, stuck on top of a pit. The site-specific installation harks back to the domestic dimension of the house, to women’s dragging journeys to fetch some water for the entire family. Women and dogs share, in fact, something more than the aforementioned domestication process: the task of guarding home and possessions, waiting for a return, that of the hero, who is, ultimately, the master: «Argo rimane sulla soglia in attesa del ritorno di Ulisse, Penelope vigila sulla casa, entrambi si consumano nell’attesa nel mentre Ulisse compie avventure, loro sono muti e ubbidienti, sono i sacrificati, gli innamorati abbandonati, i disciplinati che scompariranno nel racconto e nella storia. è dunque lo spazio domestico quello dove si consumano le vite neglette […] l’oikos, la domus, la casa costituiscono il recinto perimetrato dei rituali di addomesticamento e di canonizzazione dei ruoli»[5].

Angelo Licciardello, Toby, 2022, mixed media, 40x50x40 cm, courtesy the artist. Ph: Matteo Maino

From a heinous reinterpretation of the bond between women and dogs the decision to recover and exhibit a photographic catalog by Franco Vaccari (Modena, 1936) , which seems to have gone unnoticed by most, comes. In Cani + sedie + donne (2005), published on the occasion of an exhibition at the Municipal Art Gallery in Faenza, the Modena-based author isolates and alternates three historical subjects on the blank pages: designer chairs, dogs and women. Vaccari describes them this way: subjects that are subject to constant modifications, to sudden changes in their image according to fashions and styles: the most “distant from their immediate natures”, the closest to ongoing social changes[6]. One need only retrieve a 2021 interview for Animot to understand the origin of Vaccari’s passion-compassion for dogs: «Sono gli animali che maggiormente hanno subito la pressione degli uomini, tesa ad umanizzarli e renderli più simili a noi. Spesso ne abbiamo fatto la nostra caricatura»[7].

Franco Vaccari, I cani lenti, 1971, 8 mm video transferred to digital format, b/w and col., sound by Pink Floyd, 8’38”, courtesy the artist and Galleria P420. Ph: Matteo Maino

The danger of the “loving humanization” of our animals, “an operation that while cuddling distorts”[8], is told by the work that opens the exhibition. A dog bed built in the image of a human bed complete with quilt and backboards paints an alarming smile on our faces. Angelo Licciardello (Catania, 1990) imagines it as a votive object, dedicated to Toby, the dog from which the installation takes its title. From a small television set to the cathode ray tube placed on the ground at the end of the space, a Pink Floyd song shifts subtly: we recognize again Franco Vaccari’s signature and his I cani lenti (1971), which “with all the air of authentic poetry” wander sagging in the courts and dance on the cobblestones of Italian cities. The dog has played a fundamental role in Vaccari’s research since the 1960s when, in the Modena vista a livello di cane (1967-1968) series, the artist takes on the point of view, the “cine-eye” of the animal and invites the public to break free from the habit of photographing at human height and, rather, assume a “four-legged” framing that also returns in the first minutes of I cani lenti. “At first I had thought of attaching mini cameras on the dogs’ heads that would record what the beasts were exploring, but at the time technology was not capable of producing equipment suitable for the purpose,” the author tells Luca Panaro[9]. The importance of “perspectivism” also manifests itself in the exhibition choices: the television squashed to the ground like a pair of shoes forces us to lower ourselves methodologically, to return to our four legs, as if we had never stood upright. The dog-body, bearer of a long-silenced, torn and suffering point of view, in Vaccari’s video wanders alone through the streets, looking more and more like a black spot as we pull ourselves up away from the screen.

Franco Vaccari, I cani lenti, 1971, 8 mm video transferred to digital format, b/w and col., sound by Pink Floyd, 8’38”, courtesy the artist and Galleria P420. Ph: Matteo Maino

At the top left on the wall strikes part of a poem by Polish Nobel laureate in literature Wislawa Szymborska (Kórnik, 1923). The piece tells of an anonymous dog, which at some point finds itself abandoned by its owner, caught up in “pressing chores”. Much more than other domesticated species, the dog is a victim of stray loneliness, precisely because it is no longer able to cooperate with its own species, to form a pack with its peers, but seeks an exclusive alliance with humans: «Io che sono il cane ho provato il bisogno irrefrenabile di non voler più obbedire, sono scappato. Sono scappato alla cieca […] il corpo tornato a essere il corpo primo, quello che avevo ostinatamente divorato. […] E trovai cani che azzannavano e mangiavano altri cani, anche loro si erano perduti […] Prima o poi mi sarei dovuto fermare, per fame, paura, solitudine e abbandono […] Il corpo secondo soffre, ha paura del freddo, il corpo secondo non è in grado di procurarsi sopravvivenza, cerca il potere che lo rassicura, quello del luogo prescritto»[10]

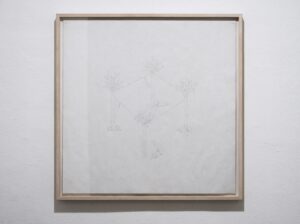

Giovanni De Lazzari, Cani dell’alba, 2012, pencil on prepared paper, 70×70 cm, courtesy the artist, Galleria Laveronica and BACO. Ph: Matteo Maino

In Cani dell’alba (2012) by Giovanni De Lazzari (Lecco, Italy, 1977) a system of wires stubbornly pulled between four trees does not allow the animals to join together as a heard. As outsiders, it is natural to surmise before the complex interplay of levers and pulls, imagining the anatomy of escape lines, the anarchic mutiny of the four beasts at the dawn of execution. They are not totally immobilized, nor is a fence immediately evident, but they can only move in the perimeter between two trees: an instrument of torture, where the more one walks, the more one explores, the more space is left for the “first body,” the more the rope around their necks is shortened.

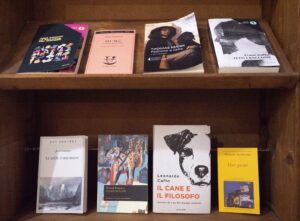

AA.VV., Literary kennel, 2022, a collection of dogs (and owners) of literature very dear to the place_e. Ph: Matteo Maino

Face-head, instincts-institutions, dog-master, nature-culture, first-body-second-body: from mapping and deconstructing these dichotomous arrangements, Padrone e cane shifts our gaze to the most recent forms of subjugation, to the delinquent presence of a control that is becoming increasingly virtual and communicative, to the mutes that – resentful – continue to bark, waiting for the opportunity to come back as a herd. The works of the 16 artists involved in the group show are alternated, in the exhibition space at 116 Via Pignolo (Bergamo), with artist’s publications, poetry collections and novels, creating a visual bibliography that gently brings out the basics of the curatorial research. At luogo_e we never stop talking: the exhibition places a very rare focus on words, narratives and production of meanings. The heterogeneity of materials, the horizontality in the choice of works and artists, and the bold juxtapositions trace a dense and timely curatorship, which transforms the exhibition into an observatory of meaning and a hub of research.

Alessia Baranello

[1] Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon. The logic of sensation, translated from the French by Daniel W. Smith, London:New York: Continuum, 2003, p.26

[2] ivi., p. 23

[3] Félix Guattari ha analizzato questi fenomeni di disorganizzazione del volto. Cfr. L’inconscient machinique: essais de schizo-analyse, Recherches, Paris 1979, pp. 75

[4] Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon. The logic of sensation, translated from the French by Daniel W. Smith, London:New York: Continuum, 2003, p. 27

[5] Tiziana Villani, Corpi mutanti. Tecnologie della selezione umana e del vivente, Roma: Manifestolibri, 2018, p. 100

[6] “Nel libro Cani + sedie + donne (2005) – un titolo che rimanda alle avanguardie artistiche del Novecento, all’associazione tra cose e persone che non sembrano avere uno stretto legame tra loro – mi riferisco a tre realtà che più di altre si piegano ai nostri desideri. I cani, le sedie, le donne. Sono soggetti a modifiche continue, risentono delle mode e degli stili, si allontanano dalle loro più immediate nature, mutano repentinamente la loro immagine a seconda dei cambiamenti sociali in corso” in Cani lenti. Franco Vaccari intervistato da Luca Panaro, Animot n. 11: L’arte per l’altro, ancora (vol.2), 2021.

[7] Cani lenti. Franco Vaccari intervistato da Luca Panaro, Animot n. 11: L’arte per l’altro, ancora (vol.2), 2021.

[8] From the exhibition guide of Padrone e cane

[9] Cani lenti. Franco Vaccari intervistato da Luca Panaro, Animot n. 11: L’arte per l’altro, ancora (vol.2), 2021.

[10] Tiziana Villani, Corpi mutanti. Tecnologie della selezione umana e del vivente, Roma: Manifestolibri, 2018, pp. 47-48

Info:

Marco Belfiore, Cinzia Benigni, Giulio Bonasone, Luca Brama, Matei Vladimir Colțeanu, Giovanni De Lazzari, Agenore Fabbri, Giovanni Fattori, Linda Fregni Nagler, Angelo Licciardello, Gabriele Longega, Edoardo Manzoni, Wisława Szymborska, Franco Vaccari, Luca Viganò, Tiziana Villani

11.11.22-14.01.23

Thursday, Friday and Saturday from 2 to 7 pm (and by appointment)

Padrone e Cane

http://www.luogoe.com

Luogo_e

Via Pignolo 116, 24121, Bergamo

Alessia Baranello (Campobasso, 1998) is an independent curator. Her research focuses on the link between visual arts and historical, social and economic issues, with a focus on experimental exhibition practices. She write about contemporary art, cultural and memory studies. She was co-curator of the artist residency Uva Program (Nizza Monferrato, July 2022) and is co-founder of the curatorial duo Scania Trasporti.

NO COMMENT