Giancarlo Bonomo, curator and art critic, from 2010 to 2013 conducted numerous television broadcasts with the Real Arte Group of Sant’Elpidio a Mare, presenting artists such as Boetti, Bonalumi, Castellani, De Chirico, Fontana, Chia. In 2013, as a collateral project of Biennale di Venezia, he signed “OverPlay” sponsored by the Consulate General of Germany. In 2015 he made his debut as an author and interpreter with the multimedia show “De Sacra Imagine” where artistic dissemination was mixed with other artistic forms such as poetry, music and prose theater. Later, in the same way, he worked on the life and works of Raffaello, Giorgione, Giambattista Tiepolo, Van Gogh, Michelangelo… In 2018, he signed the critical text and presented the exhibition “American Beauty”, the catalogue published by JULIET Editrice on behalf of the Galleria Comunale d’Arte di Monfalcone, and where authors such as Vito Acconci, Ronnie Cutrone, Mark Kostabi, Keath Haring, Andy Warhol, Federico Solmi were presented.

R.S.: Why is Italy, so rich in many works of art, struggling to give the right recognition to classical and contemporary art?

G.B.: Unfortunately the observation is very pertinent and denotes a situation that does not reflect our glorious past, not only from the point of view of creativity but also of the protection of the heritage. The answers are manifold. If on the one hand educational programs have privileged scientific training over humanities, for a series of clichés linked to the possibilities of work realization, on the other hand it must be said that the institutions have not made the best efforts for a campaign for protection and awareness. The share from the public budget that we allocate to valorization is always very small and, very often, areas of the country that are already widely known and consolidated under the promotional profile are privileged.

In critical practice, is it possible to separate the artistic work from the artist?

An attentive critic should know how to separate the human aspect from the artistic one. Often the works are dictated by an inspiration that goes beyond life itself or by unconscious reasons that the artist does not even know. The work of art, when it is such, has a communication capacity that goes beyond who conceived it. In this way we can have virtuous artists from a human point of view who nevertheless prove to be bad interpreters of themselves and of the surrounding world. Conversely, there are humanly despicable artists who are authors of absolute masterpieces. And the name of Caravaggio, for example, is there to prove it.

Can full artistic freedom exist?

Theoretically, the authentic artist should be free from dogmas, conventions and impositions or market rules. Often, however, history has shown the opposite, first with the needs of popes and princes, then with the ephemeral fashions of the artistic movements and the ‘rampant’ collecting, which defined their contours and parameters.

How close can an artist of today feel to the artists of past centuries?

Art is a concatenation of consequential events. It is inevitable that art is the mirror of the time in which it expresses itself and, in some ways, it is right to be so. It would be anachronistic for a 2020 artist to paint madonnas or angels in the manner of Giotto or Cimabue, simply because that time has already passed. However, this does not mean that today an artist does not have to consider the experiences of the past. For example, the investigation by Mauro Milani, a Bolognese artist whom I follow with particular interest, contains many references to the classical world, to Greek statues of mythological subjects with pop and dada ‘contaminations’.

Is there still in contemporary art a place for God, understood as Art that wants to go beyond the earthly dimensions?

There is always place for the divine. Lucio Fontana has demonstrated this through his famous cuts that are nothing more than windows open to infinity, in search of a possible God, even if hidden. In the new millennium God is evoked in other forms, perhaps more sophisticated and occult. For example, the painting of Sandra Zeugna, an artist very close to the informality of Zigaina, in many works evokes the concept of the divine without expressly referring to traditional figurative representation.

You are collaborating with Raffaella Rita Ferrari in organizing successful events. How did your partnership start?

About a year ago, Raffaella Ferrari proposed to me to collaborate on a project dedicated to Leonardo as part of the first edition of the Festival di Psicologia, sponsored by the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region and the University of Trieste. We created the multimedia event in November last year. Thus was born the partnership and the sharing of a common brand, Eclipsis Style Project, which intends to make an active contribution to teaching in the contemporary panorama with the creation of catalogues, critical theses and video portfolios.

What are your next commitments?

With colleague Ferrari, thematic events of contemporary painting and sculpture will take place in Bologna, which for us is the ideal showcase and city of choice! In the multimedia field we have two projects dedicated to Raffaello and Modigliani (2020 is a celebratory year for both) that we will likely propose in some squares during this summer. The first edition of I 101 di Eclipsis (National Award sponsored by the UNESCO Clubs of Bologna and Udine) will take place in the autumn.

Rosetta Savelli

Giancarlo Bonomo, all’interno della Basilica di San Giusto (Trieste), durante una lezione di storia dell’arte, ph courtesy Eclipsis Style Project

Giancarlo Bonomo, all’interno della Basilica di San Giusto (Trieste), durante una lezione di storia dell’arte, ph courtesy Eclipsis Style Project

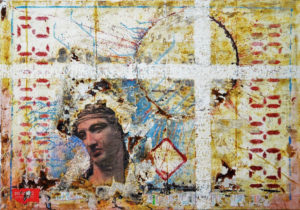

Mauro Milani, L’attesa, 2017, pittura su tela, cm 85 x 105, ph courtesy dell’artista

Mauro Milani, L’attesa, 2017, pittura su tela, cm 85 x 105, ph courtesy dell’artista

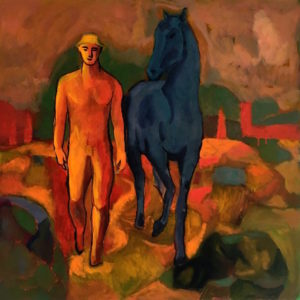

Sandro Chia, A passeggio col genio, 2016, pittura su tela, ph courtesy Miami Wynwood Art Gallery

Sandro Chia, A passeggio col genio, 2016, pittura su tela, ph courtesy Miami Wynwood Art Gallery

Enrico Castellani, Superficie viola, 2004. Ph courtesy Mazzoleni e Fondazione Enrico Castellani

Enrico Castellani, Superficie viola, 2004. Ph courtesy Mazzoleni e Fondazione Enrico Castellani

is a contemporary art magazine since 1980

NO COMMENT