We met Maria Luigia Gioffrè, founder and director of In-Ruins, a platform founded in 2018 with the aim of enhancing the relationship between archeology and contemporary art in the context of Southern Italy. Following a series of exhibitions, collaborations, and talks, Gioffrè introduces the philosophy behind In-ruins, presenting the residency program in Calabria in September 2022.

In-ruins is a unique observatory because whilst focusing on a specific cultural context, it opens up to the Mediterranean Sea acting as a lighthouse. From this privileged viewpoint, would you like to introduce us to the specific territory in which you operate?

We are a nomadic and non-profit entity and we have touched several areas of Calabria, often different from each other. We carried out activities at the Scolacium Archaeological Park in 2018 and at the Norman Castle of Squillace in 2021. This year we will be in another double location which is the Soriano Calabro Museum complex and the Villa Romana Palazzi di Casignana. From an archaeological point of view, the Roman villa is remarkable: it is managed by Sovrintendenza but is located in an environment that remains abandoned to itself. It is one, perhaps the only villa that testifies the presence of mosaics in Calabria and in Southern Italy and both this unusual place and this difficulty make the project very interesting, almost a challenge. Our artistic residences focus on research and they last almost twenty days: a limited time to develop a work of art, but more than sufficient to initiate a process. In this sense, In-ruins wants to shed a light on what has always been the cradle of culture, just think of ancient Greece. Notably, the Mediterranean is the place of production of Western philosophy, and it is important to preserve the cultural aspect of these territories, but at the same time we do not want to highlight the ruin for the sake of contemplation, but we want to make it active. This reminds me of a phrase by Franco Vaccari at the Biennale of 1967, when he stated that photography should not be contemplation, but action. It is the same relationship that we try to propose with archeology not as a cultural heritage to be contemplated, rather an action. This explains why we are so much interested in artists who work with archeology as a process, hence the archive. Furthermore, the Mediterranean is linked to the controversial theme of migration and In-ruins would like to recreate a place not only to be culturally crossed, but where to eventually land.

Your program mainly focuses on two lines of research: the relationship between archeology and art as you have already well introduced, and the theme of myth in the Mediterranean Sea. Would you like to tell us about the latter?

Much of the Calabrian archaeological heritage derives from the fact that we were a former Greek colony: we are faced with a millenary stratified history. Many of the populations that have dominated these territories have brought their culture and this has generated a vast production of myth along with minor manifestations of local mythology. Among the authors who have addressed these issues: Kuno Raeber, Ernesto De Martino, and among contemporary philosophers: Federico Campagna, who has addressed the theme of Southern magic. Why the myth, then? Surely because it is pregnant in this territory, but it is necessary to reread it from a perspective that is not static. How can this myth serve present narrations? I think of Penelope. Who is Penelope today? Also, the figure of Athena is very present in the park of Scolacium as it seems that she was the protector of the crows, very much present here. Yet, according to some readings from the Odyssey, it seems that Ulysses and Nausicaa met in the Gulf of Squillace. Who is Nausicaa today? Who are these figures? Historically, we are witnessing a deconstruction of the narrative unit and it is therefore important to recover, without falling into ideologies, the sense of individual narratives and myths. Last year, the British-Iraqi artist Emii Alrai addressed these specific features by dealing with narration and cultural encounters in her research. In this sense, we can speak of fluid identities: it is the task of our time to rediscover how identity sits within complexity where the origin is as a point to start and detach to emancipate oneself, but also a point to return to. It is a controversial discourse that however, many artists decide to face today.

How do you manage to enhance the different profiles involved, often coming from different backgrounds?

A meridian thought unites the members of In-Ruins. We are two artists directing this platform which I personally founded in 2018. Now I lead the program with my partner Nicola Guastamacchia. We share a professional training in England and what unites us is this territorial identity. We are joined by the art historian Nicola Nitido who I find to be a very precious figure as he has a knowledge not only as an artist or of contemporary art, but he is an expert of ancient and medieval Renaissance art. We are also collaborating with Roberta Carrieri, who is a curator of Calabrian origin, who now lives in France and who pursues a doctoral research on feminism in Chile and is, in some way, connected to the whole South of the world. Coinciding with the residency in September, we are also crafting a publication which collects significant contributions by artists, anthropologists, curators, and archaeologists on what is a meridian thought. In the choral space there is a unison and in this sense In-ruins responds in unison. It is almost like wanting to carry out a process of decolonization of contemporary art: in this way art is experienced in the places where that thought was born. Not to mention also, that Calabria is far from the current European geographies.

How do you respond to the interest in new technologies from an artistic and ethical point of view? Do you have any limits with respect to the medium?

We do not have any concern regarding new technologies as long as they do not betray the theoretical heart of the research. As I said that the ruin must not be anachronistic, the same is valid for the mediums an artist decide to employ in her/his practice; in this sense, technologies are favored. Ethically, we encourage research on the urgent issues of our time such as sustainability.

Are there any specific lines of research that you address in residency in this fourth edition?

Last year we gave three lines of research: individual and collective memory, the politicization of history, ruin, and the historical heritage of the Mediterranean, in addition to philology as a process, all themes that were addressed by artist Itamar Gov who revisited the Israeli ideology of the rabbis in Santa Maria del Cedro. This year we have not given specific lines that were instead addressed in the series of talks from February to April 2022, but our concept remains clear. We would like to leave the artists a little free to propose themselves within the limits of logistical feasibility, because the territory is difficult and it is not always easy to find the materials; therefore, we must interface with site-specific strategies that are necessary in this context. This is also why we favor research and this year we have entrusted the selection of artists to an external jury of experts. Another interesting aspect for this choice is to work with those artists who can truly interact and read this cultural heritage not only in relation to space, but in relation to the immaterial value of this context.

In 2022, what does “Mediterranean” mean? How does the art of these places compare with the international contemporary scene?

If I think about the Mediterranean context in 2022, I would say that this sea is fluid, certainly in a geophysical sense but more significantly because it is a symbol of fluid identities in the contemporary era, and this calls into question every conventional parameter. It is like a compass without a North and this leads to a wonderful encounter between hybrid beings whether we refer to surfing or great shipwrecks. From a cultural point of view, the Mediterranean is certainly a sea that needs to be preserved both because of its bio and cultural diversity. Its constitution is like a mosaic. A mosaic, to some extent, is similar to a puzzle: this does not want to be an attempt to put order, but to learn to hold together each different piece of the puzzle according to a joint that is exact for everybody, giving voice and space for every possibility to contribute to the great sea.

Info:

In-ruins – Residency 2022

Curated by Maria Luigia Gioffrè, Nicola Guastamacchia, Nicola Nitido

Soriano Calabro, Polo Museale di Soriano Calabro

12/09 – 24/09/2022

Casignana, Villa Romana Palazzi di Casignana

24/09 – 6/10/2022

Anna Ill Alba, Noli Me Tangere, Squillace, In-ruins residency 2021, courtesy the artist and In-ruins

Anna Ill Alba, Noli Me Tangere, Squillace, In-ruins residency 2021, courtesy the artist and In-ruins

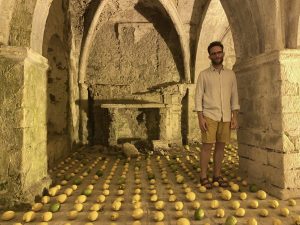

Martyna Benedyka at the Castle of Squillace, In-ruins residency 2021, courtesy the artist and In-ruins

Martyna Benedyka at the Castle of Squillace, In-ruins residency 2021, courtesy the artist and In-ruins

Itamar Gov and his installation in the gothic church of Squillace, In-ruins residency 2021

Itamar Gov and his installation in the gothic church of Squillace, In-ruins residency 2021

Anna Ill Alba in her studio, In-ruins residency 2021, courtesy the artist and In-ruins

Anna Ill Alba in her studio, In-ruins residency 2021, courtesy the artist and In-ruins

Polo Museale Soriano Calabro – Courtesy: Nicola Guastamacchia

Polo Museale Soriano Calabro – Courtesy: Nicola Guastamacchia

Performance of Ceresoli Cosco, In-ruins residency 2021, courtesy the artist and In-ruins

Performance of Ceresoli Cosco, In-ruins residency 2021, courtesy the artist and In-ruins

Emii Alrai studying the ingobbio technique, In-ruins residency 2021, courtesy the artist and In-ruins

Emii Alrai studying the ingobbio technique, In-ruins residency 2021, courtesy the artist and In-ruins

She is interested in the visual, verbal and textual aspects of the Modern Contemporary Arts. From historical-artistic studies at the Cà Foscari University, Venice, she has specialized in teaching and curatorial practice at the IED, Rome, and Christie’s London. The field of her research activity focuses on the theme of Light from the 1950s to current times, ontologically considering artistic, phenomenological and visual innovation aspects.

NO COMMENT