If being able to virtually move between Shenzhen, New York, Kinshasa, Dakar, and the border between Italy and Switzerland, all while visiting a little white cube Como-based gallery, is a sign of the times we live in, the current exhibition at galleria Ramo excels at catching the wave of contemporaneity. Yet, in this case, “moving” refers to studying borders and connections between cultures rather than familiarizing oneself with unknown territories. Although strikingly different, the works of François Knoetze and Alice Paltrinieri follow an interestingly parallel track, putting a multidimensional issue of being a human today at the center of their research.

François Knoetze

“Close your eyes, and you will see the points of light,”—suggests one of the protagonists of Dakar (2018), the first of four François Knoetze’s films from the series Core Dump. While saying it, the man puts his fingers on his eyelids and presses them to evoke the known optical effect. The gesture, seemingly too literal to be taken poetically, effortlessly becomes a multilayered illustration of Knoetze’s take on the importance of “the body [is] at the heart of political, religious, sexual, economic, and ritual power,” which, “hunts the imagination of the global West” (quotes from Joseph Tonda, a renowned sociologist and anthropologist of Congolese and Gabonese background). Investigating the notion of Digital Colonialism, Knoetze sets an intensely emotional tone to his film to tell about the plundering of raw materials, the dumping of hazardous waste, and the aftermath of this digital massacre on the people in Africa. E-waste elements are discarded all over Senegal. Most of them are recovered and burnt by local people to extract sellable lead and copper, inevitably becoming part of their bodies, “making waste of people, extracting blood, consuming dreams, and excreting misery.”

François Knoetze, “Core Dump”, 2018-2019, photographic print on Semi-Mat paper Edition 1 of 10, 84.1(h)x59.4(w)cm, image by François Knoetze, image courtesy of the artist and Galleria Ramo, 2022

The question of light is the focal point also of the second chapter, Kinshasa (2018), as it familiarizes us with the urban legend told by Joseph Tonda. Tonda’s research refers to the “multiform violence exerted on bodies and imaginations present from the earliest colonial days to the post-colonial era”, from his book Modern Sovereign, The Body of Power in Central Africa (Congo and Gabon). In the legend, a white person drives through Kinshasa at night, turning black people into pigs with the glare of the car’s headlights, which would symbolize the “animalizing violence of the lights and the colonial capitalist machine,” “blinding violence.” But Tonda’s further deduction is even more terrifying: “If the colonial Congo’s popular imagination understands the car’s dazzling lights as an animalizing force (of producing animals), there is no reason the screens of our machines should not produce the same effect. Especially since the dazzling lights of the screens reflect product/merchandise/commodities which are modern fetishes that motivate biological impulse, a compulsive desire for material wealth.” The film is based on found footage and the feature film created by the artist that not only tells the legend but also takes it a step further. The man who turned into a pig has to face another challenge. His companions don’t recognize him, are afraid of him, and try to capture him. Eventually, white people take off their white masks, revealing their pig faces.

François Knoetze, “Core Dump”, 2018-2019, photographic print on Semi-Mat paper Edition 1 of 10, 84.1(h)x59.4(w)cm, image by François Knoetze, image courtesy of the artist and Galleria Ramo, 2022

From vibrating, deeply wounded Africa, we jump to Shenzen (2019). “I want to tell you a story of greed, sacrifice, loss, and deep despair,” – recites an Asian woman in a wheelchair while playing on the instrument. She wears a blond wig and sunglasses, and her elaborate sequined outfit hides a sparkling fin. An alluring female creature inhabiting water environments is an imagery present across all cultures. In 2012, as reported in media, Chinese workers lying the cable at the bottom of the river that connects Kinshasa and Brazzaville (as if they were “tracing its [the river’s] spine with a column of light”) came across what they believed to be a divine water spirit, here known as Mami Wata. In Knoetze’s feature film, workers who captured it started treating it as their deity. One of the Mami Wata visitors, an ambitious Chinese businesswoman, asks the spirit to turn her into the wealthiest woman in Shenzen. The wish is granted but comes with conditions: not only will the deity have to be liberated, but the woman’s son will face a heavy burden; the heavier his burden, the more prosperous the woman becomes. The life of a boy ends with suicide because of the circuit boards that endlessly attach to his body, transferring the feelings (“hopes, fears, and pain”) of every worker that created them straight to his flesh. Surprisingly, while ruthless, power-hungry humans (ruling with an “iron fist”) are featured as victims of the technology they created, the humanized Mami Wata, in the film’s last scenes, enjoys the world of consumerism to the full — moving around the city and taking selfies among the newest digital gadgets.

Installation view, François Knoetze, “Core Dump”, 2018-2019, image by Simon J. V. David, image courtesy of the artist and Galleria Ramo, 2022

The last chapter, New York (2019), starts with Boston Dynamics’ study report on a Big Dog robot, a walking, perfectly agile machine tailored to the army’s needs. If given independence, this walking platform escapes, just as the loose dog would. Knoetze willingly takes his narrative from this fact. His fictional four-legs (two actors) machine moves freely around New York and gets cut in two halves while getting on a metro. Both parts, now separated and significantly weaker, wandering through the city alone, find pieces of mannequins that complete their bodies. It becomes an incentive to mention a black “Mr. Rastus Robot” (brought to life in 1931), also called a “mechanical slave,” a symbol of black servitude, which, as media news reported at the time of its appearance, “was perhaps invoked to soothe concerns around robots replacing human workers.” So it’s not only lead that researchers found to run through the blood of children in Dakar but the violation of the spiritual and mental structure of culture — “the spirit of technology is already merged with pre-colonial cultural traditions and African and diaspora sensibilities.” Knoetze’s moving images are often cut, reversed, or scattered around the screen; they flash, jump, and twirl — reflecting an anxious world challenging to grasp as a whole. The material is an accumulation of found footage, recorded interviews, and documentation of the artist’s performances that “form narrative portraits of the uncertainty in the nervous system of the Digital Earth.” In his own words, the artist focuses on the “relationship between digital technology, cybernetics, colonialism, and the re-enchanted notion of a Non-Aligned Humanist Utopia,” opening the door to a saddening reflection of the time we live in.

Alice Paltrinieri

Alice Paltrinieri uses sculpture, installation, and video to test the notion of limits, often through connecting and interacting with different locations. Currently, at Ramo, she presents a site-specific work, 9,5 km, that resembles a video-game-like experience and three accompanying images created during her summer residency in the gallery and the surrounding area. While Knoetze spots a continuous flow of connections across the globe, digging into the past and foreseeing the future, Paltrinieri has a closer look at the borders of time and space, not bothering to come up with definitions but shaping and playing with them freely instead. Her alternative way of establishing relations between time and space puts a human figure at the center, even if its presence isn’t always evident. The artist researches the boundaries that separate cultures, understanding and challenging them.

Installation view, Alice Paltrinieri, “Object in the background”, 2022, “Shadow behind head”, 2022, “Eyes fully Visible”, 2022, image by Simon J. V. David, image courtesy of the artist and Galleria Ramo, 2022

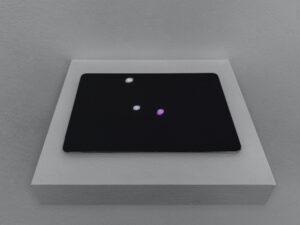

The artist’s beginnings mark the use of the medium of drawing, but it was far from standard attempts to represent an image on paper. For instance, 220 WS, 12534, NY, shown at Ramo a few years back, explores the artist’s relationship with her temporary home in Hudson (USA). The artist provides us with a “guided tour around” the house using a drawing technique called frottage that she applied to intriguing details in the house’s structure, such as its scratches, scares, and traces. This way, not only does she document the place she inhabited, creating an intimate memory of her relationship with the house, but she also “freezes” a time and space. In 9,5 km, Paltrinieri puts into practice a motion-detecting device. She takes off to the nearby border between Italy and Switzerland to trace her footsteps while walking precisely along the border line, the line that separates the two nations. As she walks, the satellite-connected light placed in the gallery shines on the white gallery walls tracing her performance. As we observe her walk sitting in the gallery by looking at the point of light moving chaotically around the screen, without the geographical or political context, what remains is a visual experience similar to a video game.

Installation view, Alice Paltrinieri, “9,5km”, 2022, image by Simon J. V. David, image courtesy of the artist and Galleria Ramo, 2022

It’s not the only time that Paltrinieri has decided to incorporate lights and sensors. In io sono qui (2022), a site-specific installation shown at Palazzo Ducale in Tagliacozzo, a 360-degree moving headlight enlightens and unveils the fresco inside the utterly dark chapel. The light moves as the GPS device tracks the artist’s routes 24/24. As a result, the visitors to the chapel can only see parts revealed by Paltinieri’s movements. The work Looking for a safe place (2022) studies the movements of both herself and her father over 30 days. Ultimately, she overlaps their trajectories, getting 63 red shapes where the two met. Each display tries to connect the shapes differently, looking for a new geography and a safe place. At Ramo, besides the video-like work, the artist displays three frames: Object in the background, Shadow behind head, and Eyes fully Visible (2022). These three works are composed of 12 passport-size frames each. Their titles come from the UK government’s precise instructions regarding the settings required to take a passport portrait photo. Paltinieri captures (screenshots) the lights from her video 9,5 km every 7 seconds. The first miniature image of each series/frame is called a Plain light-colored background and it indicates the correct way a passport image should be framed, following the gov.uk website requirements. The artist then contradicts these instructions by unifying the correct and wrong way in one frame. As in her previous works, Paltinieri creates a memory of movement and interaction, lightly incorporating the question of identity.

Installation view, Image by Simon J. V. David, image courtesy of the artist and Galleria Ramo, 2022

An enthralling angle of this exhibition stems from the contradictions between the two artists. The light — and its “repercussion,” digital devices — is nothing but evil in the entire Knoetze film series. Paltrinieri uses the light playfully, entertaining and inviting us to follow the light spot representing her movements. The enjoyable nature of video games featured in 9,5 km doesn’t fit Knoetze’s belief system either. His aversion towards the digital realm is rooted in the cruelty of Digital Colonialism he experienced. The “core dump,” as Knoetze explains in his interview with Oulimata Gueye, is the recorded state of the working memory of a computer at a specific moment in time. The computer can recall this “imprint” of its previous state to debug and recover if a crash occurs. His film series “extends the metaphor of a crash to the impending breakdown and the unsustainability of the global capitalist techno-scientific system characterized by a glut of excess and a fascination with hyper-modernity masquerading as progress.” (quote from the artist’s interview with Oulimata Gueye). One can notice that Paltrinieri’s bigger picture is based on abstract categories; she doesn’t say anything outright, doesn’t choose sides, and puts prevailing importance on the now, even if her actions extent to a certain moment in the past. Her works steer clear of the overload of collective consciousness, and the artist prefers to narrow her attention to a chosen number of people she puts under her thorough observation. Moreover, while Knoetze talks about the uncertainty in the nervous system of the Digital Earth, Paltrinieri, if she quoted McLuhan, would call telematic communication an “extension of our central nervous system”.

Info:

François Knoetze & Alice Paltrinieri, Links and fragments across memories and geographies

17/09 – 04/12/2022

Galleria Ramo, Como, Italy

Graduated in Photography and Visual Recording Arts at the University of Art in Poznan (Poland) in 2013. Graduated in Psychology from Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan in 2015. In 2018 she attended the “Latest Trends in Visual Arts” course at Brera Academy of Fine Arts. She writes art texts for various magazines in English, Italian, French and Polish. Artist, curator and researcher. Born in Poland, she lives and works in Milan.

NO COMMENT