Tarō Okamoto, a Japanese painter, sculptor and writer, famous for his paintings and abstract and experimental sculptures, was born on February 26, 1911 in Kawasaki, a city of just under 1.5 million inhabitants, in Kanagawa Prefecture, in Japan.

He has been a very prolific artist and writer until his death (Tokyo, January 7, 1996), and he had a great influence on Japanese society and culture. After entering Tokyo Fine Arts School in 1929, Okamoto found himself, almost by accident, accompanying his parents on a trip to Europe. He was greatly fascinated by Paris and its sparkling cultural life, so much so that he stayed in the ville lumière for over ten years. He studied at Panthéon Sorbonne, graduating, under the guidance of Professor Marcel Mauss, in Ethnology, focusing his studies on the typical rituals of some tribes of Oceania. Very inspired by the work of Pablo Picasso (and also for this he was called the Japanese Picasso at home), Okamoto began to be interested in Abstractionism (from 1933 to 1937, he was part of the Abstraction-Création group) and in Surrealism by André Breton and Kurt Seligman. In those years the artist was also deeply attracted to the occult and mystery cults: he attended the “Collège de sociologie” held by Georges Bataille, also participating in some mystical rites in the Saint-Germain wood, near Paris, as a member of Acéphale, a secret spiritual society.

Due to the German invasion of France, in 1940 he decided to return to Japan. It is precisely in these years of the Second World War that the idea of a total incompatibility between the two artistic movements to which he had adhered and which, until then, had considered compatible and interchangeable, began to mature. Therefore, in 1947 he introduced what will be the new core of his artistic principle, Taikyoku-ism (or polarism): an original idea of communion of opposites, defined by the art critic Ichiro Hariu as “a philosophy that asked to venture into the depths of contradictions without trying to combine them with easy solutions or compromises”.

Based on these principles and breathing the atmosphere, politically charged, of a Japan occupied by the Americans and annihilated between physical destruction and spiritual emptiness, he created some large-scale paintings such as Dawn (1948, preserved at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo) and two other mighty paintings, Heavy Industry (1949) and Law of the Jungle (1950). In the first painting Taro tells us about an era of social unrest, dismissed railway workers and about the “heavy industry” accused of reckless, rampant and unscrupulous capitalism. In the second painting, a huge, mysterious and esoteric animal with a zippered mouth launches forward threateningly as the smaller creatures try to save themselves from its fury by sneaking away the trio of wise monkeys curl up, frightened and helpless, in a corner (Kikazaru, Mizaru and Iwazaru; I don’t feel evil, I don’t see evil, I don’t speak of evil). Okamoto defined the central monster of this painting as the sinister symbolism of oppressive and authoritarian fascism.

The aesthetics underlying his art can be summarized by the words “freedom”, “pride” and “dignity”. But art alone could not enclose the lively and multifaceted curiosity of this brilliant artist. In 1964, in fact, Tarō Okamoto published a book entitled “Mysteries of Japan”: the primordial spark of this interest had been the objects of the Jōmon Period (from 10,000 to 300 B.C.) seen by him in the Tokyo National Museum. After this publication, the artist traveled across the country in search of the “repetition” of that sensation he had perceived by observing those objects and publishing, a few months later, another book, “Rediscovery of the topography of Japanese art”.

At the end of the Fifties, Okamoto began to experiment with sculptures and it is precisely with the three-dimensionality that he will be able to express himsel by creating engaging and evocative forms; among which we find what is certainly his best known work: the imposing “Sun tower” (for Expo ’70, the Osaka world fair) where the flicker of the ceremonial flame of a sorcerer, tribal totems and rationalistic principles of classical modernism masterfully blend together to represent the past, present and future of the human race.

In the 1980s an excessive media exposure (television and commercials) and an equally excessive implementation of his histrionic and bizarre attitudes had slightly negatively affected the cultural depth of his character while contributing to his fame (“Art is explosion”, the phrase that repeated during the commercial, hammering a bell he made himself, became a commonly used mantra).

But already from the Nineties his legend starts again: in 1993 he was named Honorable Citizen of the city of Kawasaki and that same year the Kawasaki City Museum makes a great retrospective of his work; in Tokyo, in 1998, his large studio in Minami Aoyama was transformed into the Tarō Okamoto Memorial Museum and the following year, an important Art Museum was entirely dedicated to him in Kawasaki. Finally, in this Museum, recently reopened after the emergency of Covid-19, the interesting exhibition entitled “Baschet Exhibition – F. Baschet and Taro Okamoto” has just ended.

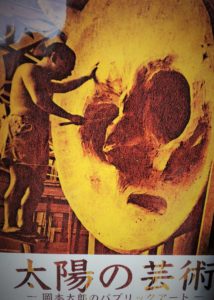

Manifesto of Tarō Okamoto at work

Manifesto of Tarō Okamoto at work

Tarō Okamoto, sculpture (detail)

Tarō Okamoto, sculpture (detail)

Tarō Okamoto, sculpture (detail)

Tarō Okamoto, sculpture (detail)

All photos were taken by Angelo Andriuolo (© 2020) at the Taro Okamoto Memorial in Minami Aoyama (Tokyo), the artist’s home / studio

The passion for art convinced him to become an entrepreneur in the art market. Gallerist and Art Promoter, he worked in Italy and Turkey, curating, among other things, the organization of over 100 exhibitions. From 2016 he moved to Tokyo.

NO COMMENT