In 1941 Jacques Gelman, a Russian jew escaped from the October Revolution, meets and marries Natasha Zahalkaha in Mexico City and two years later commissioned Diego Rivera the portrait of his wife thus enshrining the beginning of a deep friendship and of a collection that will bring together the works of the greatest Mexican artists of the period. The exhibition presented in Bologna by Arthemisia Group curated by Gioia Mori traces the cultural and politics events during the Mexican Renaissance through the works of the Gelman collection obtained on loan from the Fundación Vergel Cuernavaca. The common thread is made up of the love story between Diego and Frida Kahlo and their acquaintances with the other artists who gravitated around the affluent couple of patrons who built their fortune as movie producers of comedies.

The exhibition opens with a series of portraits of Natasha Zahalkaha among which those made by Diego and Frida stand out: while the first depicts her wrapped in an elegant evening dress that opens in corolla echoing the shape of the large calla lilies that surround her, the second portrays the charming blonde lady like a Hollywood diva with a thoughtful look that is a fitting introduction to her analytical and introspective attitude. The comparison shows how much Frida’s artistic conception was antithetical to that of her husband: if Diego in easel paintings deals with the same popular themes of his monumental works by binding the art to a precise social and political function, Frida opposes the collective post revolutionary epic a lyrical and intimate poetic that embodies the melancholy joy of the Mexican soul.

The Riveras ostentatiously performed their Communist faith but they had a controversial political identity: in 1937 they housed in Casa Azul Leon Trotsky and his wife Natalia but some time later Diego was suspected of being part of the Stalinist conspiracy that had orchestrated the first attack on the Russian leader and had to flee in the United States, the capitalist country par excellence, where he had achieved success and money for his murals which challenged the American economic ethics. Similarly Frida was attending with her husband the demonstrations of Mexican workers using her own body in ante litteram performances, such as the one documented by the click of Florence Arquin in which the artist wears a bust of plaster decorated with the hammer and sickle, but her life style that was not above the bourgeois comfort was often picked on by the international press.

The most authentic sap of her art lies instead in her painful personal stories, the serious car accident that hopelessly compromised her health when she was a young woman and the tormented relationship with Diego, her increasingly pervasive obsession in a fluctuating succession of resentments, betrayals and reconciliations . Her body, battered by surgery and abortion is the focus of a series of works in which Frida paginates herself as if she were the subject of an anatomical table, drawing the diseased organs (the broken spine, the barren womb and the swaddled foot) in a visionary naturalism in which visible veins and umbilical cords become narrative and symbolic devices. The analysis of the details punctuates each stage of acceptance of a destiny vowed to atonement that finds its meaning in the artistic expression seen as the only possible form of redemption.

The most intense core of the works in the exhibition is centered on a series of self-portraits in which Frida inscribes her inner biography elaborating her own myth in the intersection between the worship of herself and the celebration of her native land. Her folkloric clothing is an accurate statement of identity and an ideological manifesto through which she returns integrity and dignity to Mexican imagery to export it to Europe and North America in a metaphorical reverse colonization. Adorned with flowers and showy jewelry as an Aztec deity, she portrays herself surrounded by objects and animals that become fetishes and attributes of her habits and her personal affairs. So dolls and monkeys allude to her unattainable desire for motherhood explaining at the same time with the eloquence of their looks the mistress’s mood while her intricate hairstyles become love calls routed to Rivera as in Self-Portrait with braid in which the hair form the infinity symbol to establish the inevitability of their bond. Merciless in describing herself in the paintings she refines the features of Diego returning her inner vision or she transfigures his features transforming his fixed idea into an idol as is the case of The loving embrace of the Universe where the union of Frida and her spouse characterized by strange childhood likeness appears in the center of a cosmic embrace.

An extensive photo section is a counterpoint to the paintings comparing them with the look of the many photographers who documented the life of the famous couple and who found in Frida their muse. These shots, in addition to providing passionate testimony of their intense relationship and the tenacity with which Frida faced her physical infirmities turning them into beauty, are a further confirmation of her innate ability to ritualize her official image in order to personify the cultural heroine that his people needed acclaim. By staging her difficult existence in an inextricable tangle of aesthetic refinement, communicative intelligence and disarming introspection, Frida seems to be ahead of the vocation to behavior and icon that a few years after her death would twist traditional aesthetics canon in an unrepeatable blend with fine and popular painting at the same time. As evidence of the continuing influence of her style and her creative language, the exhibition concludes with a selection of recent works created by artists and designers who have been inspired by her legendary figure reinterpreting in a contemporary way some suggestions.

The Gelman collection: Mexican art of the twentieth century.

Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo, María Izquierdo, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Ángel Zárraga

curated by Gioia Mori

November, 19 2016 – March, 26 2017

Palazzo Albergati

Via Saragozza 28, Bologna

Frida Kahlo a Coyoacán. Foto di Gerardo Suter

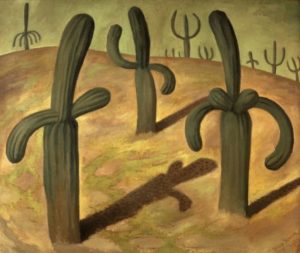

Frida Kahlo a Coyoacán. Foto di Gerardo Suter Diego Rivera, Paesaggio con cactus, 1931, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Foundation, Cuernavaca © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México D.F. by SIAE 2016

Diego Rivera, Paesaggio con cactus, 1931, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Foundation, Cuernavaca © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México D.F. by SIAE 2016

Frida Kahlo, Autoritratto con treccia, 1941, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Foundation, Cuernavaca © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México D.F. by SIAE 2016

Frida Kahlo, Autoritratto con treccia, 1941, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Foundation, Cuernavaca © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México D.F. by SIAE 2016

Frida Kahlo, L’amoroso abbraccio dell’universo, la terra (Messico), io, Diego e il signor Xolotl, 1949, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Foundation, Cuernavaca © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México D.F. by SIAE 2016

Frida Kahlo, L’amoroso abbraccio dell’universo, la terra (Messico), io, Diego e il signor Xolotl, 1949, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Foundation, Cuernavaca © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México D.F. by SIAE 2016

Frida Kahlo, Autoritratto con scimmie, 1943, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Foundation, Cuernavaca © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México D.F. by SIAE 2016

Frida Kahlo, Autoritratto con scimmie, 1943, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Foundation, Cuernavaca © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México D.F. by SIAE 2016

Graduated in art history at DAMS in Bologna, city where she continued to live and work, she specialized in Siena with Enrico Crispolti. Curious and attentive to the becoming of the contemporary, she believes in the power of art to make life more interesting and she loves to explore its latest trends through dialogue with artists, curators and gallery owners. She considers writing a form of reasoning and analysis that reconstructs the connection between the artist’s creative path and the surrounding context.

NO COMMENT