Undoubtedly Živko Marušič is a cornerstone of “Slovenian” figurative painting, starting from its debut, in the late Seventies. I put in quotation marks his peculiar belonging to a national tradition because, although for strange vicissitudes of the life he was born in Colorno, at the beginning of the Eighties he had his atelier in Koper. In those years he participated as a protagonist in the cultural renewal that in a not yet free Slovenia, but already in the odor of an imminent separation from the centralized state, was carried on by Toni Biloslav and Andrej Medved, the first as president and the second as director of the Coastal Galleries.

But Marušič, before being part of a society or a cultural current, is a great imaginative, a great inventor of narratives and iconographic hybrids, intrinsic qualities and inherent in undoubted pictorial and creative qualities.

Now, we go through the process of his work in a dialogue with the author.

In the Eighties you took part in the exhibitions of the New Slovenian Image; what do you remember of those ferments and that strong desire to anticipate the fall of the physical blocks that still separated Europe into two economic and political realities?

The critical work of Andrej Medved was important because it gave the opportunity to exhibit to young artists throughout the former Yugoslavia and also to have international contacts. All with the help of two art historians: Zvonko Maković (Zagreb) and Ješa Denegri (Belgrade).

Thanks to this activity of strong renewal you met Achille Bonito Oliva and you have been included in the book on the “Transavanguardia internazionale”, published by Giancarlo Politi…

They were fundamental years but, momentary applause aside, all these “Ex Super Boys” are like dry grass today.

I remember that your pictorial material of the Eighties was dominated by a fascinating figuration, with white masses fraying in convulsive brushstrokes of color: a charged and solid pigment. A visionary and complex painting, not separated from daily details and chronicles, quotationism (I think Picasso), cultural references (I think of Emilio Mazzoli and the painting you dedicated to him), and a great interweaving of stories and figures. Can you tell us a few words about those years and how you lived them?

At the turn of the Seventies and Eighties there was a great interest in new and fresh things: a real nourishment to feel happy. In those days there were no boundaries for me and art made everyone happy, including collectors. Thanks to the support of a small group of collectors, I managed to live with the daily financial crisis. However I want to emphasize that the Eighties were BEAUTIFUL, although they abused me: if at the Venice Biennale they would have included me in the Yugoslavian pavilion my prices would have gone up, instead my prize was this sentence that I still keep behind me: “Yours don’t want you either”. But who are “my supporters” I do not know.

For those years, do you think it is possible to talk about “Zeitgeist” that merges with a fall in history, or an awareness of one’s present minute that forgets a broader and more complex vision? In your case, can we talk about the mythology of everyday life? Do you like this definition?

Really, I do not know. I feel a little outside of any definition. What I remember is that the first push, however, gave me the exhibition I made at the Center of the Chapel in Trieste, in 1982.

Former Yugoslavia and Slovenia afterwards, have always experienced a shortage with regard to the structured art market on the filter of gallery owners and collectors. How did you manage to survive in this kind of desertification?

Today, Slovenia is full of painters who would like to return to painting, despite having never learned it at the academy. Teaching them about painting now is impossible because they never leave the iPhone. Surviving is the right word because it makes us understand the difficulties of everyday life. The world is full of ruffian art dealers, a bit art dealers and a little jackals, and they are all half a notch. These merchants “without head or brain”, incite you to work even for the sake of rubbing them.

How is your research going now? What are your support points in Slovenia and Croatia, where you have ultimately moved for some years? And above all, how do you see the current cultural situation of those areas where you still love to live and from which you never wanted to separate?

For me painting has always been the most mysterious thing, and it allows you to dream, not caring about thieves, whores, manipulators, dealers, balls. But ultimately today’s art is like yesterday’s and we are all repeating students: it is like staying in the first class with teachers who change, and who are differently dressed each time, while their mind in understanding is always the same.

Živko Marušič, Araki, 2006, pigments and wax on canvas, 300 x 300 cm

Živko Marušič, Araki, 2006, pigments and wax on canvas, 300 x 300 cm

Vista parziale della mostra alla Equrna Gallery, Ljubljana, December 2012. Photo by Arne Brejc, courtesy Equrna Gallery

Vista parziale della mostra alla Equrna Gallery, Ljubljana, December 2012. Photo by Arne Brejc, courtesy Equrna Gallery

Živko Marušič, Cheap dreams, 2011, pigments and wax on canvas, 200 x 300 cm. Photo by Arne Brejc, courtesy Equrna Gallery

Živko Marušič, Cheap dreams, 2011, pigments and wax on canvas, 200 x 300 cm. Photo by Arne Brejc, courtesy Equrna Gallery

Živko Marušič, Talking Tomatoes, 2018/19, pigments and wax on canvas

Živko Marušič, Talking Tomatoes, 2018/19, pigments and wax on canvas

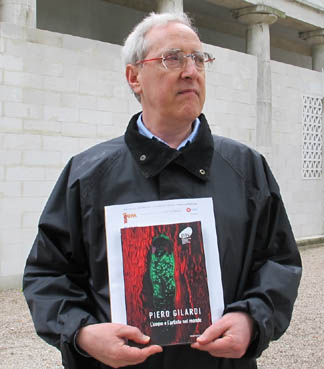

He is editorial director of Juliet art magazine.

NO COMMENT