The unreachable, fertile, home-studio of Olimpia Biasi stands out against a grey-white, February, Treviso horizon. Unreachable, by length, a pink gauge to which the green of her famous garden draws near, a living wall against a predictable winter background. And precisely there inside, as in a stables, the works in preparation may be seen, or the gaps of those already running in some museum, like the works for the Orto Botanico in Padua, collected under the name of Viriditas, on display until 1 May 2018.

But it is a continuous play of contrasts, that of Biasi who, precisely in the exhibition under way at the Orto Botanico, promoted by Padua University, intends recounting the primordial and perpetual strength of the herbs, the slimes, the insects that populate and animate that ‘viridity’ imprinted rather in very light supports made of filaments and gauze through which the air passes, nourishing a dry microcosm and keeping it alive. And there could be no more evocative place than the Hortus Patavinus (first university botanical garden in the world, dating from 1545) for staging this solo exhibition of the Treviso artist, curated by Virginia Baradel. Biasi’s works are thus put into dialogue with the father of gardens, placed in the exhibition areas inside (the gauzes, the herbariums, the drawings, the canvases) and outside, with three installations inserted between plants, trees and water.

Wherever they are placed, these works live on the contrast in seeing them hung and light, though tied to a symbology that, where it is not ominous and heavy, is very powerful in expressing the vitality and cosmic expression of being. And so that thread sewn between leaves and butterflies becomes a connecting thread with Hildegard of Bingen, the mystical German from whom come the threads of the imagination that, put alongside the manual and attentive practice of female work and culture, inspire Biasi’s last works’, writes the curator. Female nature itself evolves and doubles with this feminine work expressed in the work of Olimpia Biasi, from the use of thread to cultivation, from the collection of seeds to the weavings of herbs. The artist’s interest flows naturally into many other works, like the Diari imprinted with graphite that suggest Frida Kahlo, the suffering, exhibitionist freaks of Diane Arbus or Hildegard herself. A constant style is fortunately not evident in all the works hung on the wall, resting against the walls or on the tables; there are big monochromatic canvases, expertly filled as in the Cielo calpestabile series, where the poetic value of the celestial extension is shattered, by now parcelled out and catalogued according to the impracticable measures of aircraft or cadastres.

The transformation occurs suddenly, colour immediately gives way to drawing, now tendential, completely cross-current at the moment of execution. But those dismembered animals return to recompose Biasi’s panels, foxes, eagles and mice in a hunt for the red between the signs of graphite, which define the connotations of Homo-homini-lupus. It is those same signs that then turn into construction iron to give shape to the fine spirit of a butterfly ‘interlined’ in the way that that sewing thread goes back to being the narrative conductor of a total work, as artisanal as it is irremediably linked to thought and word. ‘But the art of an artist should not be peremptory’ says Olimpia Biasi, and she says it as if it were the only true law in which she believes, in doing and in appreciating that which is around her.

‘There are those who have this fever’, she continues, ‘a damnation and a magic’, that of wanting to express the world in other ways and to think themselves able to make it derail. A hope and, it seems, a wish, because Biasi admits it: ‘I get bored with always seeing and doing the same things’. And so here is the magic of art, to continuously discover an orient, but behind a panel or a canvas; it is precisely the portraits that surprise Olimpia Biasi, in what she herself defines as an ‘inventing of people’. And that sewing thread returns, which becomes incision or brush in bringing back a know-how now lost in tendency and repetition. A thread capable of reuniting the centuries, from the Crusades to the contemporary, in pearls or leaves of different faceting but of the exact same size. An artistic collection, vague imprint of a utopia, and, precisely as herbariums must have been for doctors, a drug to turn a pang into something less painful.

Roberta Durante

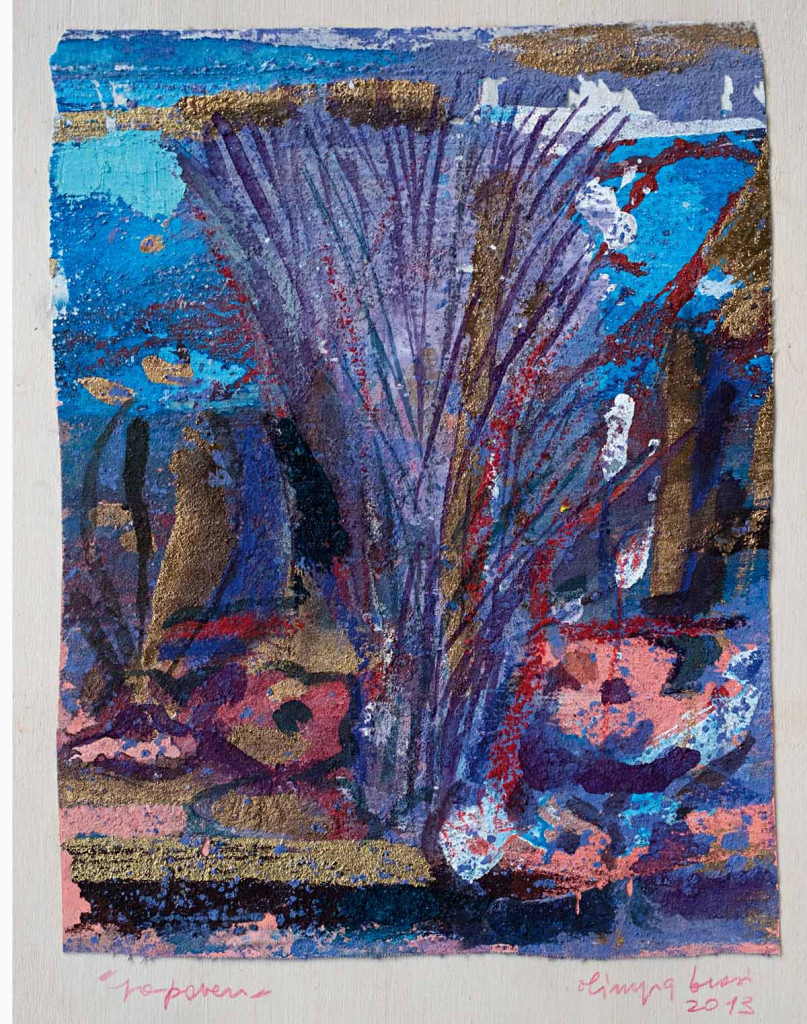

Olimpia Biasi, Paradisi, 2015, mixed technique on paper, private collection

Olimpia Biasi, Paradisi, 2015, mixed technique on paper, private collection

Olimpia Biasi, Erbari, 2015, mixed technique on paper, private collection

Olimpia Biasi, Erbari, 2015, mixed technique on paper, private collection

Olimpia Biasi, Garza dei semi e delle foglie (detail), 2017, multi-material collage on gauze, private collection

Olimpia Biasi, Garza dei semi e delle foglie (detail), 2017, multi-material collage on gauze, private collection

Author and journalist from Treviso. She has published Girini with which she won the Mazzacurati-Russo award (d’if, 2012), Club dei visionari (Di Felice, 2014), Balena (Prufrock spa, 2014), La susina (d’if, 2015) and the audiobook Nella notte cosmica (Luca Sossella, 2016).

NO COMMENT