Utopia, from the Greek (ou-topos), means ‘non-place’ or ‘a place that does not exist’, impossible to reach, where everything goes right and good prevails (eu-topos). The goal is unreachable but the mere attempt to get closer to this place leads to an improvement. In contrast, dystopias are defined as those dark places where nothing goes right, symbolically corresponding to catastrophic prophecies that serve as a warning: without an immediate change, the future will inevitably be disastrous. The change that is being asked right now, transversally and almost unanimously, demands for a sustainable model of development that can counteract the climate crisis, that can look, even if from far away, to a possible new utopia.

Piero Gilardi, Mele cadute nella neve, 1967, expanded polyurethane, 70 x 100, private collection, courtesy Dep Art Gallery, Milano

The exhibition Utopiche seduzioni (Utopian Seductions) curated by Matteo Galbiati and Nadia Stefanel at the Fondazione Dino Zoli in Forlì investigates the relationship between art and environmental emergency with a special focus on the material, leading to a comparison between different generations of artists and a review of the value attributed over time to certain materials: what seemed innovative in the past has in most cases turned out to be a curse for the new generations. The exhibition establishes a dialogue between the works of nineteen contemporary artists (ranging from sculpture to two-dimensional works, from photographs to site-specific interventions, all marked by a new awareness and sensitivity towards the environment) and the ‘vintage’ works by Piero Manzoni, Piero Gilardi and Enrico Baj, for whom plastic and polyurethane represented progress. The common trait is a renewed approach to matter distinguished by a research and experimentation through recycling and reuse of waste or through the use of natural substances. Through the artists’ ideas and know-how, the material is transfigured, it becomes something else: in some cases it retains its recognizability by explicitly recalling the climatic emergency, in other cases it can be deduced only after a careful observation, and at other times it no longer bears any trace of what it was at the beginning.

From left to right: Margherita Levo Rosenberg, La violazione, from the Garofanie series, 2023, decofix x-ray films, approximately 90 x 80 x 30 cm; Piero Manzoni, Achrome, 1961-62, fibreglass, 61.5×46 cm. Ph. Agostino Osio © Piero Manzoni Foundation, Milan

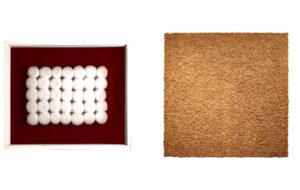

A significant example is Margherita Levo Rosenberg‘s ‘Violation’, in which a mass of violet filaments forms a sort of bramble bush, somewhere between the branching of a coral and an alien vegetable. Reading the caption, one discovers that the material making up the work is obtained from discarded X-ray plates carefully cut into thin strips, then knotted together. It is a precise choice on the part of the artist, who intends to delve deep inside and bring to light what is covered by both physical and psychological stratifications. Complementary to Purple is ‘Giallo Consumo’ by Michele di Pirro, an artist for whom the reuse and recycling of materials is essential. The work appears as a mustard-coloured square with a fibrous, dense and soft surface. In this case, it is the smell that reveals the material: getting closer, one feel a strong odour of smoke and realizes that the yellowish carpet is obtained from the juxtaposition of acetate wads made from cigarette filters. The artist has personally collected the butts and cleverly applied them to a layer of Velcro: it is a denunciation gesture, but also an example of how one of the least noble materials imaginable can be elevated to the status of art.

Da sx a dx: Piero Manzoni, Achrome, 1962, pallini di ovatta, 20×27 cm. Ph. Bruno Bani © Fondazione Piero Manzoni, Milano; Michele Di Pirro, Giallo consumo, 2023, tecnica velcro, acetato di cellulosa (filtri di sigaretta recuperati), 150 x 150 cm

The Transfiguration occurs also in the case of Giulia Nelli, who takes over the spaces of the Dino Zoli Foundation with a large black perforated web. From here, a sort of asymmetrical latticework departs, whose filaments – or tentacles – seem to cling where they find space. ‘Life in the Folds of the Earth’ is the result of the recycling of polyamide and elastane tights, reorganised into a new body that invites us to reflect on how everything is interconnected and on the fact that the only hope is cooperation. The use of fashion industry waste also accompanies the Afran’s work, who rethinks denim with ‘Redemption of the Sacred’: seven head-shaped sculptures made from old jeans. The artwork suggests a similarity both with African masks – recalling the artist’s origins – and disturbing faces from a post-apocalyptic future. The author reshapes fabric and reworks loops, buttons and zips that become faces details of the depicted entities. The subtitle of the exhibition says: ‘From new materials to recycled art’. But in the case of those who work with textiles, it would be better to speak of upcycled art. This practice, which originally indicated “making with what one has” through the creative reuse of objects no longer useful in crisis situations, later became a means of personal expression in the sphere of hippie and then punk countercultures, and then took on the status of a true creative approach that questions the concept of the new and finds infinite possibilities by limiting its action field to second-hand materials.

Giulia Nelli, Vita nelle pieghe della terra, 2023, collant nero di diverse densità (den) dell’azienda Elly Calze e tessuto di lino, installazione site-specific, dimensioni ambientali

The Belgian Martin Margiela, whom the New York Magazine described as the reincarnation of Duchamp in the form of a fashion designer, was already turning blankets into coats, old jeans into dresses and socks into jumpers in the 1990s. Rather than father of the ready-made, based on a re-use approach, the Belgian designer could perhaps be considered more a pioneer of upcycling, and as such a subverter of the axiom new=beautiful. In this sense, the difference between art and fashion, which, similar in attitude, draw on the same materials while resulting in different objects, is blurred. If we all bought second-hand or recycled clothing, this would have a substantial positive impact on the environment. Similarly, art becomes an active agent in elaborating concepts, critiques and proposals regarding environmental issues, with particular reference to climate change: it can become a model, a vehicle for ideas, an experimentation field or simply an index.

Afran, Riscossa del sacro, 2023, sculture polimateriche, plastica, metallo, cuciture di Denim, installazione di sette elementi, dimensioni variabili

Recycling is the practice of turning waste back into raw materials, and it is fundamental for Sasha Vinci, an artist who is careful to produce objects in an environmentally friendly way using recycled materials or organic pigments. Vinci, in this case, takes the alabaster needed for his installation from the waste of a master craftsman. “You don’t draw the sky, Volterra canto I” is composed of 21 slabs of the mineral arranged in a luminous strip that shows the engraving of Volterra’s skyline on a musical pentagram. The resulting melody resonates in the exhibition spaces.

Sasha Vinci, Non si disegna il cielo Volterra Canto I°, 2015, installazione site-specific Palazzo dei Priori, alabastro, legno, luce, suono, 525 x 15 x 70 cm

Lulù Nuti‘s ‘Autoproduction’, on the other hand, recycles waste plaster, cement and metal from past projects left in her studio. The result is a sculpture, a lectern with a spine that holds its own history inside. At the top is a small book containing photographs of family jewellery and other works arranged according to a specific juxtaposition rhythm. Recovery can also occur through the concept that what is discarded, forgotten or erased returns to light in a new form, making memory alive. Also for Marina Gasperini waste becomes as interesting as the work itself, as in the case of ‘Red Flag’. Starting with recycled textile materials, namely a bright red Chanel rag, the artist carves the inscription “Anger is a Political Atlas” with the intention of using the letters for an urban performance in the city of Brussels, but then it is the cutout mask itself that becomes an art work, overlapping the boundaries between positive and negative.

Marina Gasparini, Bandiera Rossa, 2022, ritaglio e ricamo su tessuto, 140 x 275 cm

The second part of the exhibition’s subtitle says ‘From Piero Manzoni to the latest generation’. Sixty years have passed, but one difference is certain: in the 1960s, time seemed infinite and the future radiant, while the current generation appears pervaded by anger, oppressed by questions that are not given answers, it is a generation that seems to implode for fear of being the last. The title of the exhibition seems to refer to the utopian seductions from the past, but it can also be interpreted in the present: the works on display also suggest the possibilities of art to create models and propose solutions that can seduce mankind, now aware of the climate emergency, towards sustainable development.

Info:

AA.VV., Utopiche Seduzioni. Dai nuovi materiali alla Recycled Art. Da Piero Manzoni alle ultime generazioni

Curated by Nadia Stefanel and Matteo Galbiati

28/10/2023 – 24/03/2024

Fondazione Dino Zoli

viale Bologna 288, Forlì

www.fondazionedinozoli.com

Born in Bologna, he studies fashion design and multimedia arts at the IUAV in Venice. He believes in the possibility of crossing boundaries between disciplines and that art can have an active role in breaking down inequalities and uniting people by creating communities.

NO COMMENT