The story of Vivian Maier, a talented self-taught photographer who immortalized US society of the economic boom in lively street shots between the ‘50s and the ’70s, is still largely shrouded in mystery and her impressive photographic archive, which emerged a dozen years ago in fortuitous circumstances, it is a fascinating case of posthumous rediscovery that reinvigorates the romantic myth of the lonely and misunderstood artist who entrusts the survival of his work to destiny.

Vivian was born in New York in 1926 from a French mother and an American father of Austrian origin; following the separation of her parents, she and her mother are guests for some time by Jeanne Bertrand, an established photographer who transmits her passion to the two women. After spending a few years in France, Vivian, who bought a professional Rolleiflex camera in 1951, thanks to the liquidation of an estate that had been left her, moved permanently to the United States, first to New York and then to Chicago, where she works as a nanny and dedicates all her free time to shoot and develop in an amateur darkroom. Reserved and shy (not even the families where he worked and lived were aware of her artistic secret), she walks the streets of the popular neighborhoods in search of atmospheres, details, attitudes and forms that coincide with her personal vision of the world and that she holds in travel cases without showing them to anyone. With age and the occurrence of serious financial difficulties, she moves to a sanitarium and her belongings, deposited in a warehouse box, are auctioned off due to unpaid rents. The young John Maloof redeems them as a whole in 2007: struck by the surprising iconographic treasure (thousands of photographs and hundreds of film rolls and negatives still to be developed) that he finds among the junk of a lifetime, he begins to share those images on social networks and on photography web sites and to look for the author. He will never be able to track her down and Vivian dies in 2009 without knowing that the box had been expropriated and that her work was traveling the world and acquiring more and more admirers.

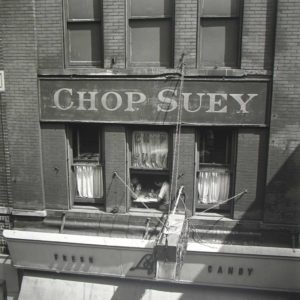

The exhibition at Palazzo Pallavicini, curated by Anne Morin and promoted by Pallavicini srl, brings together 120 black and white shots and a selection of 20 color photos taken in the ’70s when the artist replaced the Rolleiflex with a Leica, which was much lighter and with the lens at eye level. The exhibition itinerary is divided into thematic sections that highlight the multiplicity of points of view with which Maier observed street life: childhood, portraits, architecture, social classes, shapes, colors and self-portraits in which the artist reflects and confuses herself in the urban landscape. Each shot, in whose style it is possible to see echoes of the photographic avant-garde of the time (from Lisette Model to Diane Ardus, Walker Evans, Andrè Ketèsz and other artists of which it is spontaneous to ask if she knew the work), focuses on a particular aspect of the visible to return instantaneity as a balanced and original composition. The anonymous multitude in the streets is for Maier an inexhaustible source of interest and beauty for her peculiar attitude to pay attention to not usually considered aspects, in a period when street photography was in its infancy.

Her privileged subjects are the exponents of the lower social classes, of which she manages to condense the gestures in picturesque scenes with a cinematographic cut that never lead to caricature due to the profound understanding and empathy with which the artist aligns herself with what she sees. In every wrinkle, grimace and deformity she is able to read and transmit the story of a life, the struggle for survival, the daily pursuit of happiness of those who must work hard so as not to be overwhelmed by difficulties. At the opposite extreme there are the shots dedicated to the upper class bourgeoisie, whose characters appear as fleeting appearances on luxury cars that when they realize they are being photographed react with an unaesthetic arrogance to the invasion of her gaze. In an intermediate limbo are placed instead the children, identified as a peculiar human category that responds without class distinction to the behavioral codes of childhood, but also as a parallel community of future adults whose destiny can already be prefigured by observing the physiognomic analogies and behavior that lead them back to their families. Vivian, made invisible by the reserved attitude and the inconspicuous appearance, uses photography as a way to relate to the outside and for her to relate means to get closer to what arouses her interest up to blend in the forms and atmospheres that only the her sensitive lens manages to grasp.

In this way even the most abstract and formalist shots always seem to reflect her thought or state of mind, while the frequent self-portraits that show her reflected in a shop window, in a shiny surface or even in a mirror that some porters are unloading from a van, are a tool of resistance to the indistinct flow of things and an attempt to find her place in a world where she may have always felt a bit foreign. Regardless of the passing of time and fashions, Vivian continues to look in the camera with the same impenetrable and enigmatic gaze, making us realize how loneliness was a choice and revealing the independence, far from being obvious in those years, of a woman capable to find her center in herself and in her great passion.

Info:

Vivian Maier

curated by Anne Morin

Palazzo Pallavicini

Via San Felice 24 Bologna

2018, March 3 – May 27

Vivian Maier, Self-portrait, undated, copyright Vivian Maier Maloof Collection

Vivian Maier, Self-portrait, undated, copyright Vivian Maier Maloof Collection

Vivian Maier, July 1957, Chicago Suburb, copyright Vivian Maier Maloof Collection

Vivian Maier, July 1957, Chicago Suburb, copyright Vivian Maier Maloof Collection

Vivian Maier, March 1954, New York, copyright Vivian Maier Maloof Collection

Vivian Maier, March 1954, New York, copyright Vivian Maier Maloof Collection

Vivian Maier, Untitled, 1953 copyright Vivian Maier Maloof Collection

Vivian Maier, Untitled, 1953 copyright Vivian Maier Maloof Collection

Graduated in art history at DAMS in Bologna, city where she continued to live and work, she specialized in Siena with Enrico Crispolti. Curious and attentive to the becoming of the contemporary, she believes in the power of art to make life more interesting and she loves to explore its latest trends through dialogue with artists, curators and gallery owners. She considers writing a form of reasoning and analysis that reconstructs the connection between the artist’s creative path and the surrounding context.

NO COMMENT