At the beginning of the 1930s the illustrated press had reached a culminating point, with the publication of magazines with photographic reports from every corner of the world through which readers could travel with their minds and feel witness to what was happening in places that they would never have been able to see firsthand. The multiplication of images on the printed paper had created photojournalism, a new way of documenting reality with iconic images in which the synthesis of the moment, the aesthetics and the point of view of the author converged into exemplary episodes that condensed a more broad socio-epochal conjuncture. For several decades, two generations of ethically and socially engaged photographers, such as Lewis Hine, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa, fathomed in their shots the soul of an era, sensing its conflicts, contradictions and enthusiasm. In this group of great signatures of photography we also find the American W.Eugene Smith (1918-1978), to whom the MAST Foundation dedicates a major retrospective on the centenary of his birth, presenting his most ambitious and suffered project, a monumental portrait through images of Pittsburgh, (Pennsylvania, USA), the most famous industrial city of the early twentieth century.

Smith began his career when he was very young, moving to New York a year after his father’s suicide to work as a freelancer for the Black Star Agency, through which his shots were published in the most important magazines of the period. From 1944 he began traveling as a war correspondent for LIFE, documenting the horrors of Okinawa and Iwo Jima; he returned home when he was seriously wounded in the face by a grenade and after two years of rehabilitation and painful interventions, in 1947 resumed working full-time for the magazine. Some of his most famous reportages date back to that period, such as The Country Doctor, which tells the daily life of the doctor Robert Ceriani, Nurse midwife dedicated to the work of a black woman from the deep south or Spanish Village realized in Deleitosa in Extremadura that describes the life of the most marginalized social strata during the Francoist dictatorship.

Smith, obsessive in his search for perfection and profoundly idealistic, considered the reportage as a mission, whose aim was to awaken consciences on the world’s critical issues to trigger real political and social change. This is why all his works are designed to arouse intense emotions, evoke dark and dramatic atmospheres played on strong chiaroscuros and present the lives of anonymous protagonists as memorable events that will build history. What interested the artist was to fathom and make visible the essence of human existence through fragments of reality that through the filter of his gaze and his objective became symbolic images, universal archetypes of the inconsistencies and yearnings of modernity. Severus with himself and intransigent with others, he soon came on a collision course with the magazine for his chronic delay in delivering the work and for his constant dissatisfaction with the layout of the press and the texts that accompanied his photos.

So at the age of thirty-six, at the maxiumum of success and notoriety, after a quarrel decided to leave LIFE to join the Magnum agency, hoping that independent work would give him the opportunity to express himself with greater freedom and to realize his dream of authenticity and perfect harmony between images and words. The occasion seemed to arrive with the first commission by the French agency, the request to realize within a couple of months a hundred photographs of the skyscrapers and industries of Pittsburgh for a publication celebrating the bicentenary of its foundation with a text by Stefan Lorant. But immediately the intentions of the clients and those of the photographer turned out different and the latter found himself trapped by his subject in the utopian ambition to create a definitive and absolute portrait of a sprawling city-organism of which he wanted to capture all the aspects without leave out nothing. After two years of fierce dedication that caused the collapse of his finances and irreparable disagreements with his wife and children who left him alone, he was forced to declare himself defeated, to surrender to the impossibility of grasping an ever-elusive totality in an inexhaustible sequence of specificity specimens.

The products of his monumental commitment (almost 20000 negatives and 2000 masterprints) are currently collected in the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh and now part of that project – 170 vintage prints accompanied by autograph excerpts that tell his artistic flair and his observations and discovered in his photographic “body to body” with the city – is visible for the first time in Italy in the MAST Gallery. The images describe the complexity of Pittsburgh with a syncopated rhythm, they penetrate the streets and the factories to offer a distillation of the photographer’s experience that was incurably fascinated by the black soul of the steel city, the faces of the workers, the production systems, from urbanism and the contradictions of the social fabric.

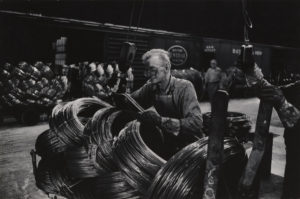

In Smith everything is spectacular and dramatically emphasized: the epic beauty of the blast furnaces that stand out against the burning black and white skies mindful of Turner, the artificial lights of the evening reflected in the waters of Ohio, the electric pylons that disappear between the fumes the chimneys lost in dense Leonardesque nuances, the signs on the great buildings that seem to disorient rather than indicate the direction, the bourgeois solidity of the institutional buildings. And again the workers, impersonal creatures when they wear masks and protective visors during the shift, faint shadows in the backlight in the immeasurably large spaces of the factories, types coming from the slums of every nation united by starvation wages, strikes and exploitation. And their children playing in the street and watching the activities of adults, women mothers and workers, the library as a place of refreshment and perhaps social redemption, the harshness of a landscape that absorbs the individual transforming it into an internal gear .

These images let emerge the profound empathy with which the photographer approached his subjects, his stubborn will to understand to offer his contribution in terms of civil commitment, the excessive emotional involvement that was perhaps the reason of the failure of the exhaustiveness of a project that today, after more than half a century, is able to open a powerful glimpse into the America of the ’50s between lights, shadows and promises of happiness and progress, showing us how, his goal to reach the essential had been achieved.

Info:

Eugene Smith: Pittsburg. Portrait of an industrial city

May 17 – September 16 2018

curated by Urs Stahel

MAST

Via Speranza 42, Bologna

W.Eugene Smith, USA, 1918-1978 Steelworker, 1955-1957 gelatin silver print 23.49 x 33.34 cm Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh Gift of Vira I. Heinz Fund of the Pittsburgh Foundation © W. Eugene Smith / Magnum Photos

W.Eugene Smith, USA, 1918-1978 Steelworker, 1955-1957 gelatin silver print 23.49 x 33.34 cm Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh Gift of Vira I. Heinz Fund of the Pittsburgh Foundation © W. Eugene Smith / Magnum Photos

W. Eugene Smith, USA, 1918-1978 Mill Man Loading Coiled Steel, 1955-1957 gelatin silver print 22.86 x 34.61 cm Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh Gift of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, Lorant Collection. © W. Eugene Smith / Magnum Photos

W. Eugene Smith, USA, 1918-1978 Mill Man Loading Coiled Steel, 1955-1957 gelatin silver print 22.86 x 34.61 cm Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh Gift of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, Lorant Collection. © W. Eugene Smith / Magnum Photos

W.Eugene Smith, USA, 1918-1978 Steel mill, 1955-1957 gelatin silver print 34.29 x 22.86 cm Carnegie Museum of Art, PittsburghGift of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, Lorant Collection, © W. Eugene Smith / Magnum Photos

W.Eugene Smith, USA, 1918-1978 Steel mill, 1955-1957 gelatin silver print 34.29 x 22.86 cm Carnegie Museum of Art, PittsburghGift of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, Lorant Collection, © W. Eugene Smith / Magnum Photos

W. Eugene Smith, USA, 1918-1978 Girl leaning on a parking meter, Shadyside Chamber of Commerce carnival, Walnut Street, 1955-1957 gelatin silver print 33.66 x 22.22 cm Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh Gift of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, Lorant Collection. © W. Eugene Smith / Magnum Photos

W. Eugene Smith, USA, 1918-1978 Girl leaning on a parking meter, Shadyside Chamber of Commerce carnival, Walnut Street, 1955-1957 gelatin silver print 33.66 x 22.22 cm Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh Gift of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, Lorant Collection. © W. Eugene Smith / Magnum Photos

Graduated in art history at DAMS in Bologna, city where she continued to live and work, she specialized in Siena with Enrico Crispolti. Curious and attentive to the becoming of the contemporary, she believes in the power of art to make life more interesting and she loves to explore its latest trends through dialogue with artists, curators and gallery owners. She considers writing a form of reasoning and analysis that reconstructs the connection between the artist’s creative path and the surrounding context.

NO COMMENT