This online edition offers the possibility of sharing William Kentridge’s contribute to my written panel into the role of the private archives of creatives which was published in the last printed issue of “Juliet”, along with other authoritative testimonies and an introductory text which motivates the new service. Furthermore, it gives the possibility, to those who wish, to listen to his answers in English and to visualize more images.

For this panel I have contacted this genial artist again, because, in addition to being a leading player amongst the most active and representative protagonists of the international art scene, he makes his own archive a laboratory of experimental creativity, from which a multimedia production of high aesthetic and ethical quality derives.

It is to be remembered that Kentridge makes tradition and innovation, historical and contemporary culture, claiming and transcendence; traditional and new technologies; visual arts, literature, cinema, music, dance, theatre, installation, performance et al interact cleverly. A mix of components able to involve the viewers in a multi-sensory, poetic and emotional sense, stimulating a deep reflection on the socio-economic, cultural and political reality of our times. Thus his spiritual and material mission acquires a universal value.

The main source of his work, aristocratic and popular, is the past and present human condition in South Africa (where he lives and works), but he also addresses, always with strong civil commitment, a wider range of issues, not only geographically speaking, such as inequality and injustice, marginalization and slavery of yesterday and today, and wars which cause disastrous consequences.

In the following interview – released by an audio file in the aftermath of the world premier inauguration of his complex performance at the enormous Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern in London – he reveals unpublished aspects of the archival practice and his operating method

William Kentridge [who answers by audio file]: This is a message from Kentridge to Luciano Marucci This is from my studio in Johannesburg on a cold Thursday evening the 19 July 2018.

Your questions about the archive are much too estrous for me. I’m happy to keep the questions as they are and put them in a file of raw material to use when doing the project about artists interrogating themselves about things they don’t understand and, as such, this list of questions will become part of my archive, but perhaps it’s useful if I just talk for a few minutes to you about my sense of the archive. So the first layer of my archive is in 3 places. It’s in cardboard boxes which have old photographs. I guess, from the 1990s and backwards when I used to print out photographs that are a mixture of personal photographs, sometimes things cut out of newspapers, photographs I have taken myself that were printed to postcard size, some black and white photographs and next to them is a set of drawers which have different phrases on different pages of books that I’ve used in different projects. These sit in the studio as a kind of constant source of raw material and in that sense they’re both an archive of projects that have been done in the studio: my archive as an artist which, as you say, is of interest to curators now but also an external archive which I raid when working on new projects for phrases, for words.

The second element of the archive is a shelf which has all the notebooks which are for the last many years a uniform black Moleskine notebook in which there are some drawings, but mainly texts and notes and phrases which have amassed over the years on which I’m working on the whole time and there often again they form a record of the work as an archive of things made in the studio, but also as raw material to be paged through and raided for different projects – many words from one project migrate to another. It used to be until recently that going to the archive to hunt for things meant going to the library and paging through books which either I would do or one of my studio assistants would do. Now it almost always means just trawling through the internet. I need an Italian gas mask from 1915; instead of hunting through whole books, about the First World War, I put in “Italian gas mask from 1915” and 4.000 images come up on Google, so as a resourceful reference images, I use the internet a lot, but that archive disappears – images from that never become part of my archive ‘cos they’re glimpsed on the screen. Occasionally I would print out an image but by and large they would disappear into the cloud and become as impersonal as anything, so the traces which are still physical, sketches of notes, of family photos or other photos I’ve taken as references for work have a very different quality as an archive and so I do understand when curators get interested in that trace of the pre-digital in the work. I’m not sure how much this directly affects whether I’m working in multidisciplinary ways or not. The resources that I raid range obvionsly from listening to music, to reading news items, to reading academic articles to hunting for images; it certainly gets thinned out by using the internet, in that one is less likely to come across something that has nothing to do with your subject but which is on the next page of an encyclopedia which you might get caught by.

Question 4: Is it the place where you practice the inventive hybridization of interactive multimedia techniques?

Absolutely not. That gets done in the studio. The archive is a set, it’s maybe two shelves in the studio which would get taken out of the box, put on the table and so into the studio, and till it’s visible and handy for me it doesn’t feel that it’s entered into the process of making, except in a distant way, in the sense of knowing there are books that cover these topics. When I work on a new project, generally I find a lot of books either in my library in the house and bring them into the studio, covering the Russian Revolution, the First World War books that I’ve read for other purposes which for the duration of the project come into the studio and I guess form an archive of what we are looking at, with the other people in the project and they’ll get put back in the library when the projects finished. And the hybridization of which I presume in the many different forms at work whether it’s music, or dance, or drawing or projection is the work of the studio; it’s the work of the performers and participants and collaborators and musicians the dancers rather than an archive; well although we may look to the archive for details, or reference to how a dance was done or what a music sounded like.

Question 6: Currently are the elements necessary to create multifaceted themed works taken mostly from your rich physical documentation and from everyday experience or from the Web?

It’s a mixture, it’s a mixture of things which are found on the web, but the most recent project about Africa in the First World War” [The Head & The Load, performance on South-Africans during W.W.1 held last July, Turbine Halle, Tate Modern. London] we found some images of carriers as a reference on the web but the history of the First World War was mainly on books, one or two articles on the web, a lot of visual references; yes, if I needed to see what the face of John Chilembwe [Baptist pastor and educator (1871-19015), an early figure in the resistance to colonialism, celebrated in Malawi on January 15 as a hero of independence] looked like, I would find that on the web, so yes it’s definitely an important part of it. I know that some curators are interested in the physical objects that artists have surrounded themselves by and part of my piles of photos and notebooks that I’ve described have infact gone out to an exhibition, but I hope they’ll come back and sit on the shelves where they should. I’m not sure if this answers your questions about the place of the archive.

Question 1: Do the documentation and the collective memories that you use for your works tend to teach observers to reflect on the socio-cultural reality of the present and to imagine the future?

I’ve no idea, you would have to answer that.

Question 2: Can they also stimulate new ideas?

The artwork does, whether it’s the archive or the documentation doing it I couldn’t say. The documentation is important for the artwork and the artwork is important for people to make a connection to what’s being shown to them.

Ok. I hope this answers some of your questions and that it gives you enough information about the archive.

It’s been very nice talking to you and I wish you good evening.

curated by Luciano Marucci

(Transcription from audio recording in English by Serena Fioravanti sent from Anne McIlleron of the William Kentridge Studio)

[The Italian text is also included in “Estetica ed Etica degli Archivi Privati. Il ruolo della documentazione fisica in era digitale”, “Juliet” art magazine n. 189, pp. 34-43, October-November 2018. To listen to the artist’s answers in English activate the audio file.]

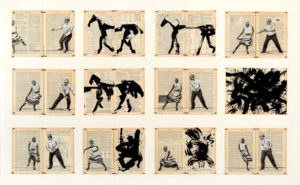

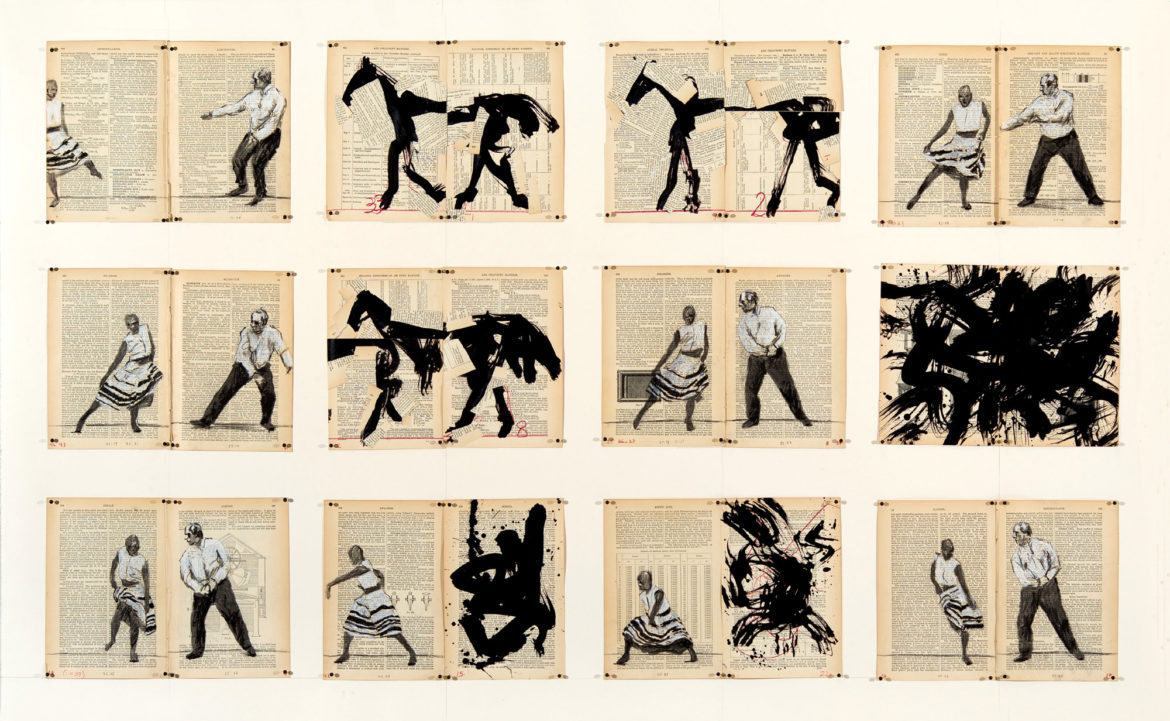

William Kentridge, “Double ports”, 12-2013

William Kentridge, “Double ports”, 12-2013

Drawings for “Tango for Page Turning”, 2013 (detail)

Drawings for “Tango for Page Turning”, 2013 (detail)

Working table in William Kentridge’s Johannesburg studio, 2010

Working table in William Kentridge’s Johannesburg studio, 2010

William Kentridge working with Gerhard Marx on sculptures for the film “Return”, 2008

William Kentridge working with Gerhard Marx on sculptures for the film “Return”, 2008

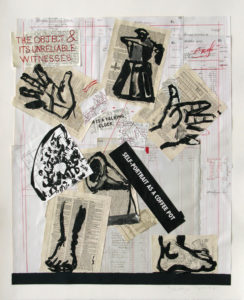

WK, “Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot”, 2012

WK, “Self-Portrait as a Coffee Pot”, 2012

Workshop for “The Head & the Load, Johannesburg”, 2017 (ph Stella Olivier)

Workshop for “The Head & the Load, Johannesburg”, 2017 (ph Stella Olivier)

I’m Luciano Marucci, born by case in Arezzo and I look my age… After a period in which I dedicated myself to journalism, applied ecology, environmental education and traveling the world, I occasionally collaborated as an art critic with specialized magazines (“Flash Art”, “Arte & Critica”, “Segno”, “Hortus”, “Ali”) and with varied cultural periodicals. Since 1991 in “Juliet” art magazine (in print and edition) I have regularly been publishing extensive services on interdisciplinary topics (involving important personalities), reportages of international events, reviews of exhibitions. I have edited monographic studies on contemporary artists and book-interviews. As an independent curator I have curated individual and collective exhibitions in institutional and telematic spaces. I live in Ascoli Piceno.

NO COMMENT